UPDATE: Changed the title from “the value of the right approach” to “the value of a different approach” – thanks to Aaron for the nudge!

I was thinking about how to respond to this. I found myself wanting to share rhetoric tips, so I’m posting this as a blog entry instead of a comment. =)

On my post about the Manila Zoo, Anna commented: “Don’t you love animals? Then why are you eating them? What’s the difference between the animal that you ‘love’ and the animal that is on your plate? If you really love them, you’ll stop having them for dinner.”

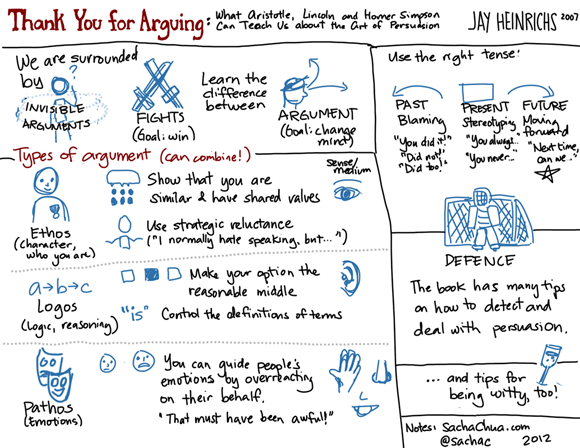

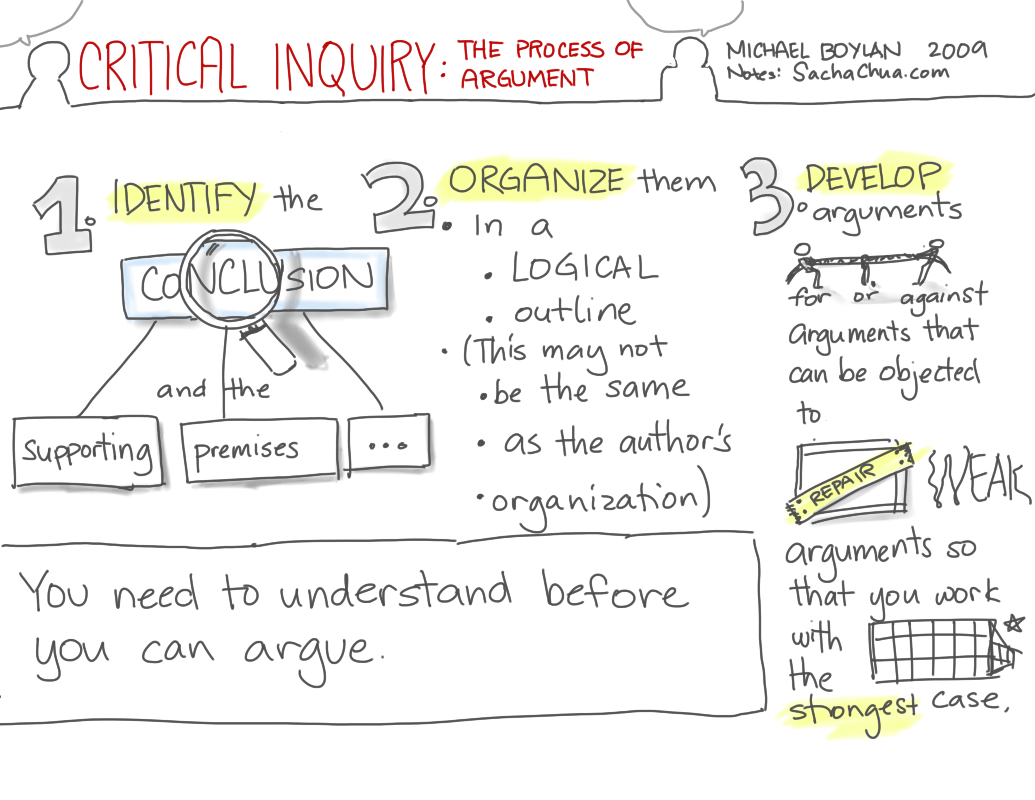

One of the benefits of learning about rhetoric and argument is being able to recognize what’s going on. Here, Anna tries to set up a dichotomy: either you love animals and are vegan, or you eat animals and don’t love them. Relying on such a premise weakens Anna’s case. I don’t have to accept this premise, and I can see other choices.

This looks like an inarguable situation: she’s not going to convince me to adopt a vegan diet through these words, and I’m probably not going to convince her to be more precise and more compassionate in her rhetoric. But I’d like to explore this anyway, because there’s something interesting here about the difference between what she’s trying and how I’d do it. (When life gives you lemons, write a reflective blog post about them!) If I were in Anna’s shoes and I wanted to nudge someone to move towards a more plant-based diet, here’s what I would try.

—

You can very rarely make someone do something. If you want to influence someone’s behaviour, you have a much better chance if you can inspire them rather than if you criticize them or force them. Part of that is building a bridge between the two of you so that the other person can understand and listen to you, and part of that is helping the other person imagine how much better their life would be with your proposal.

I know that can sound frustrating and slow. There have been many times I wished I could just wave a magic wand (or write a program!) to get people to change their behaviour, understand a new concept, or stop e-mailing huge files around. But in all the books I’ve read and through all the coaching I’ve done, I keep coming back to these lessons again and again: you can’t change people’s minds for them, and influencing cooperation can be much easier than sparking conflict.

So I would start by building common ground, instead of approaching it antagonistically. This is a common mistake for radicals, influencers, and people carried away by their passions. Goodness knows I’ve got enough examples of doing this myself in the early years of my blog. When you get stuck in an “us versus them” mindset, it becomes difficult to connect with people in a compassionate, respectful manner. Instead of trying to imply that the person I’m talking to hates animals or is hypocritical, I’d probably start off by highlighting things we have in common. Something like this: “I’m happy to see you love animals a lot.” This validates what the other person has said, affirms them, and starts off on a positive note.

Then I would use personal experiences as a bridge, showing people I’ve been where they are and they can relate to me. If you want to make it easier for people to see what you see, you need to show them that you’ve stood where they stand, acknowledging challenges along the way. That way, you can connect with people and help them be inspired. In this hypothetical argument, it might be something like “I love animals too, which is why I’ve been shifting to an all-plant diet. It’s sometimes hard to stick with it, particularly when I’m hanging out with friends, but it’s easier when I remember the troubles animals go through and the kind of world I’d rather build for them.”

I’d soften the call to action. People don’t like being manipulated by false dichotomies or preachy advice. I would probably explore the waters with a question like, “Have you thought about shifting to a vegetarian or vegan diet, too?” By backing off a little, I acknowledge the other person’s choices and reasons instead of trying to make decisions for them.

Depending on whether I thought it was necessary, I might include some social proof or alternative reasons. For example, plant-based diets can be healthier and less expensive than diets with a lot of meat. They can have a smaller environmental footprint, too. It’s good to anticipate and acknowledge the difficulties. Growing plants isn’t automatically guilt-free: see the clearing of land to support commercial agriculture; the dangers of monoculture, fertilizers, and pesticides; the consequences of transportation.

I’d end by showing my respect for people’s choices and finishing on a positive note. This would be a good place to thank the person again and highlight common ground, remembering that the goal isn’t to score points, but to open up a possible conversation enriched by personal experience.

—-

So here’s what that might look like, if I wanted to influence someone to eat more vegetables and fewer animals.

Before: “Don’t you love animals? Then why are you eating them? What’s the difference between the animal that you ‘love’ and the animal that is on your plate? If you really love them, you’ll stop having them for dinner.”

After: “I’m happy to see you love animals a lot. I love animals too, which is why I’ve been shifting to an all-plant diet. It’s sometimes hard to stick with it, particularly when I’m hanging out with friends, but it’s easier when I remember the troubles animals go through and the kind of world I’d rather build for them. Have you thought about shifting to a mostly-vegetable, vegetarian, or vegan diet, too? I’ve found that it usually comes out cheaper than my old meals, and I feel healthier and more energetic too. Hope to hear from you soon!”

Your mileage may vary, of course. You might feel that this more compassionate I’m-on-your-side approach is too mild for you. I present it as an alternative, so it’s easier to see that not all advocacy has to be confrontational.

—

Having reframed the comment in a more positive tone, what would be my personal response to it? I’m aware of the arguments for and against vegetarianism and vegan diets. I do eat mostly vegetables, thanks in part to a community-supported agriculture program that keeps me busy figuring out what to do with zucchini, in part to concern over what goes into the food that goes into us, and in part to a stubborn frugality that dislikes paying the premium for steak. I don’t think I’ll ever follow a strict vegetarian or vegan diet, though, because I don’t like inconveniencing friends and family, or proselytizing at the kitchen table. I’ll follow my own decisions when it comes to food I can control, but I’ll try to go with the flow when it comes to what people share with me. (I still opt out of balut and other things that make my mind boggle, although many people consider such things delicacies.) So even this tweaked message isn’t going to make my decisions for me, but it will leave me with more respect than aversion to how people try to get their messages across.

Parting thoughts: If you come to a conversation prepared for a fight, that’s what you’ll get. If you come to a conversation with love and compassion, you’ll have more opportunities to learn and grow. It’s amazing how much of a difference your starting point can make. It takes practice to be able to consider different approaches and choose one that fits, and, if necessary, to translate what other people say into what they might have meant. Hope to help more people think about and consciously choose how to approach conversations!