Learning to work on my own things

Posted: - Modified: | experimentMy annual review showed me that despite my resolution to reduce consulting and focus more on my own stuff in 2014, I actually increased the amount of time I spent working on client projects than I did in 2013 (12% vs 9%). Sure, I increased the amount of time I invested in my own productive projects (15% of 2014 compared to 14% in 2013) and the balance is still tilted towards my own projects, but I’d underestimated how much consulting pulls on my brain.

This is the fourth year of my 5-year experiment, and I’m slowly coming to understand the questions I want to ask. In the beginning, I wanted to know:

- Do I have marketable skills?

- Can I find clients?

- Can I build a viable business?

- Can I get the hang of accounting and paperwork?

- Can I manage cash flow?

- Can I work with other people?

- Can I deal with uncertainty and other aspects of this lifestyle?

- Can I manage my own time, energy, and opportunity pipeline?

After three years of this experiment, I’m reasonably certain that I can answer all these questions with “Yes.” I’ve reduced the anxiety I used to have around those topics. Now I’m curious about other questions I can explore during the remainder of this experiment (or in a new one).

In particular, this experiment gives me an rare opportunity to explore this question: Can I come up with good ideas and implement them?

I’m fascinated by this question because I can feel the weakening pull of other people’s requests. It’s almost like a space probe approaching escape velocity, and then out to where propulsion meets little resistance and there are many new things to discover.

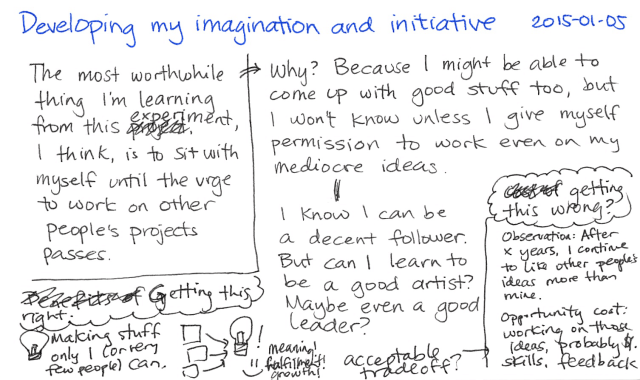

The most worthwhile thing I’m learning from this experiment, I think, is to sit with myself until the urge to work on other people’s projects passes. Arbitrarily deciding that Tuesdays are no longer consulting days (leaving only Thursdays) seems to work well for me. I find that I can pick things up readily on Thursdays. The rest of the time, I think about my own projects. Mondays and Wednesdays are writing days, Tuesdays are coding days, and Fridays are for administration and wrapping up.

Last year, I found it easy and satisfying to work on other people’s requests, and harder to figure out what I wanted to do. It’s like the way it’s easier to take a course than it is to figure things out on your own, but learning on your own helps you figure out things that people can’t teach you.

What’s difficult about figuring out what I want to do and doing it? I think it involves a set of skills I need to develop. As a beginner, I’m not very good, so I feel dissatisfied with my choices and more inclined towards existing projects or requests that appeal to me. This is not bad. It helps me develop other skills, like coding or testing. Choosing existing projects often results in quick rewards instead of an unclear opportunity cost. It’s logical to focus on other people’s work.

One possibility is to build skills on other people’s projects until I run into an idea that refuses to let go of me, which is a practical approach and the story of many people’s businesses. The danger is that I might get too used to working on other people’s projects and never try to come up with something on my own. In the grand scheme of things, this is no big loss for the world (it’ll probably be all the same given a few thousand years), but I’m still curious about the alternatives.

The other approach (which I’m taking with this experiment) is to make myself try things out, learning from the experience and the consequences. If I’m patient with my mediocrity, I might be able to climb up that learning curve. I can figure out how to imagine and make something new – perhaps even something that only I can do, or that might not occur to other people, or that might not have an immediate market. Instead of always following, I might sometimes be an artist or even a leader.

What would the ideal outcome be? I would get to the point where I can confidently combine listening to people and coming up with my own ideas to create things that people want (or maybe didn’t even know they wanted).

How can I tell if I’m succeeding? Well, if people are giving me lots of time and/or money, that’s a great sign. It’s not the only measure. There’s probably something along the lines of self-satisfaction. I might learn something from, say, artists who lived obscure lives. But making stuff that other people find remarkable and useful is probably an indicator that I’m doing all right.

What would getting this wrong be like? Well, it might turn out that the opportunity cost of these experiments is too high. For example, if something happened to W-, our savings are running low, and I haven’t gotten the hang of creating and earning value, then I would probably focus instead on being a really good follower. It’s easy to recognize this situation. I just need to keep an eye on our finances.

It might also turn out that I’m not particularly original, it would take me ages to figure out how to be original in a worthwhile way, and that it would be better for me to focus on contributing to other people’s projects. This is a little harder to distinguish from the situation where I’m still slowly working my way up the learning curve. This reminds me of Seth Godin’s book The Dip, only it’s less about dips and more about plateaus. It also reminds me of Scott H. Young’s post about different kinds of difficulty.

As a counterpoint to the scenario where I find out that I’m not usefully original and that I’m better off mostly working on other people’s things, I hold up:

- my Emacs geekery, which people appreciate for both its weirdness and their ability to pick out useful ideas from it

- the occasional mentions in books other people have written, where something I do is used to illustrate an interesting alternative

So I think it is likely that I can come up with good, useful ideas and I can make them happen. Knowing that it’s easy to get dissatisfied with my attempts if I compare them with other things I could be working on, I can simply ignore that discomfort and keep deliberately practising until either I’ve gotten the hang of it or I’ve put in enough effort and must conclude that other things are more worthwhile.

If you find yourself considering the same kind of experiment with freedom, deciding between other people’s work and your own projects, here’s what I’m learning:

It’s easy to say yes to other people’s requests, but it might be worthwhile to learn how to come up with your own.