W- and I are getting married in less than two weeks. In preparation for that (and as a way of keeping sane during the pre-wedding hullabaloo), we've been learning how to argue. You've gotta love a man whose reaction to a challenging situation is to not only figure how to address the conflict, but also to learn more about effective communication.

You might be thinking: Isn't rhetoric about political grandstanding, slick salesmanship, and mouldy Greeks and Romans? Isn't “argument” just a fancy word for “fight?”

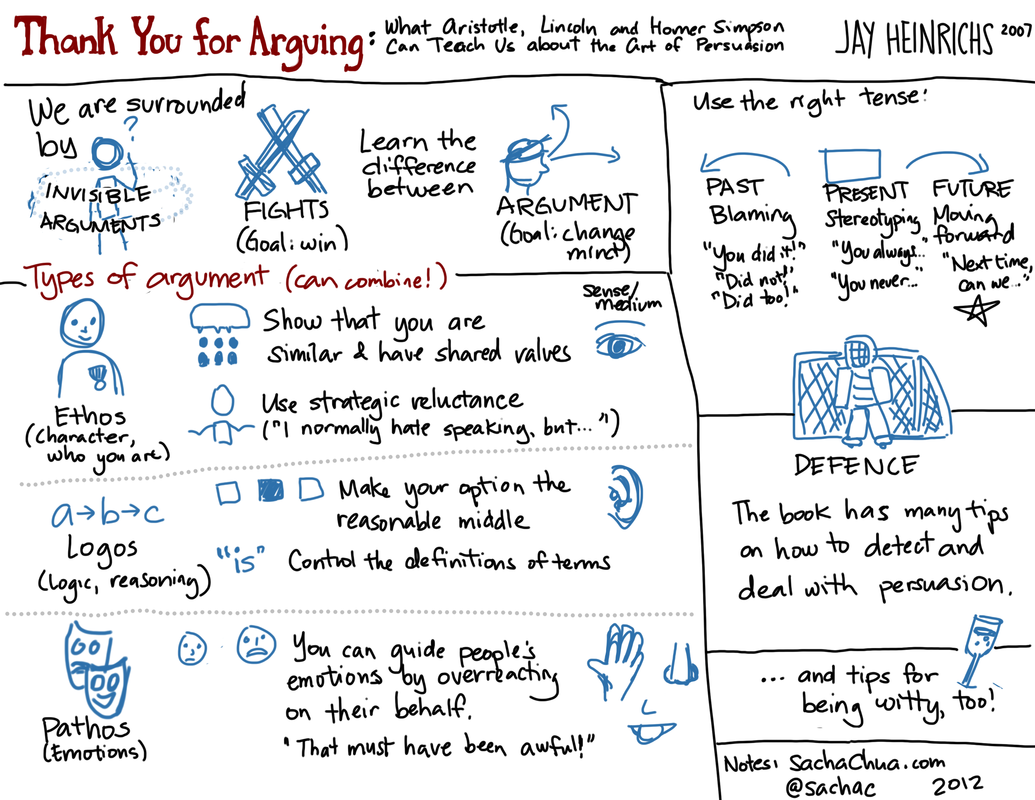

I thought so too, non-confrontational me. It turns out that learning more about rhetoric and argument can make relationships even better. In “Thank You for Arguing: What Aristotle, Lincoln and Homer Simpson Can Teach Us About the Art of Persuasion,” Jay Heinrichs points out the difference between fighting to win and arguing to win people over. What's more, he uses familiar situations drawn from everyday life: persuading his teenage son to get him toothpaste, defusing potential fights with his wife, and analyzing the selling techniques and marketing tactics that beseige us.

My first encounter with Heinrichs was when W- pointed me to Heinrichs' post on “How to Teach a Child to Argue.” It's a clever example of logos, ethos, and pathos. Reading it, I thought: Hey, this is so practical. Then I wondered: Why didn't I learn this in school? But I brought myself firmly back into a focus on the future by asking: What can I do to get better at this? When Heinrich writes about the past (forensic), present (demonstrative), and future (deliberative) tenses of arguments, I recognize my own urge to focus on moving forward–practical things we can do–during difficult conversations that threaten to spiral into blame games or overgeneralizations. Learning more about rhetoric helps me understand the patterns, working with them without being sucked in.

It isn't easy to admit to learning more about rhetoric and argument. One downside of reading mybooks on communication and relationships as a child was that people occasionally doubted if I meant what I said. As a grade school kid, I found it hard to prove I wasn't being manipulative. It's still hard even now, but at least experiences give me more depth and reassurance that I'm not just making things up. I like Heinrichs' approach. He and his family are well aware of the tactics they use, but they relate well anyway, and they give each other points for trying. I'm sure we'll run into unwarranted expectations along the way – learning about argument doesn't mean I'll magically become an empathetic wizard of win-win! – but I'd rather learn rhetoric than stumble along without it.

Besides, argument – good argument, not fights – could be amazing. In “Ask Figaro“, Heinrichs writes:

“My wife and I believed that happy couples never argued; but since we started manipulating each other rhetorically (we recognize each other's tricks, which just makes it all the more fun), we've become a happier couple.”

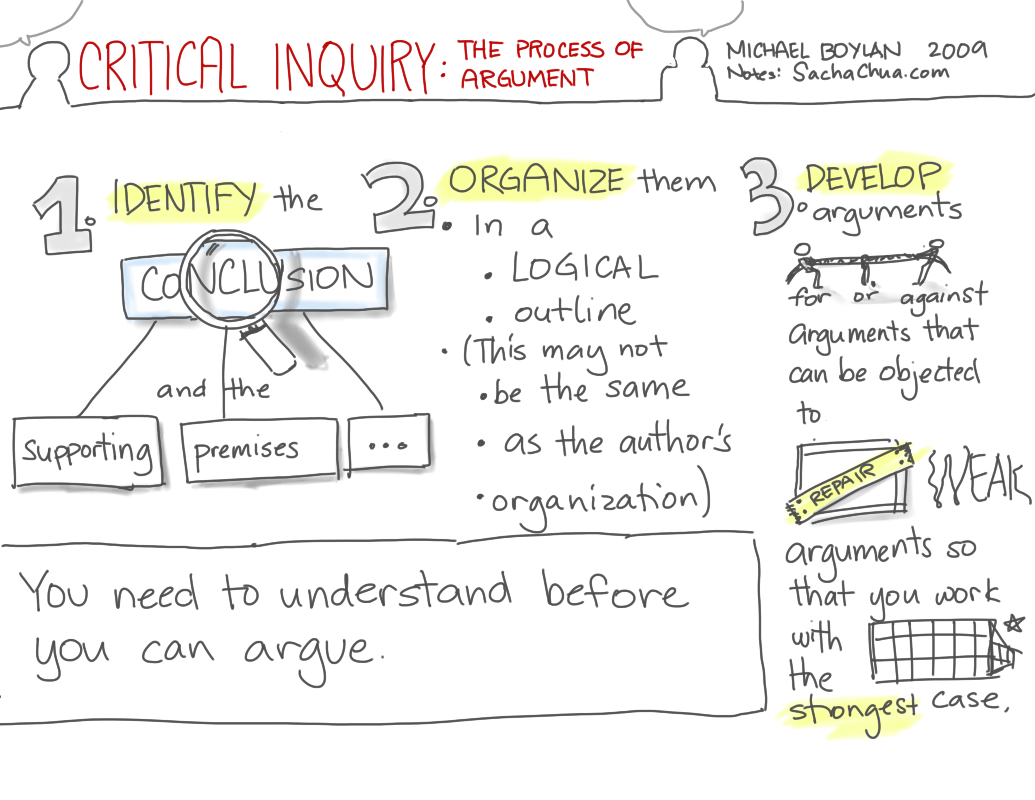

To learn more beyond “Thank You for Arguing”, we've also raided the library for other rhetoric books. Nancy Wood's “Essentials of Argument” is a concise university-level textbook with plenty of exercises that I plan to work on after the wedding. “Critical Inquiry: The Process of Argument” also promises to be a good read. These are not books to skim and slurp up. They demand practice.

Results so far: I have had deeper conversations with W-, had a still-emotional-but-getting-better conversation with my mom (I'm getting better at recovering my balance), and conceded an argument with Luke about dinner. (It's hard to argue with a cat who sits on your lap and meows – pure pathos in action.) I'll keep you posted. I look forward to practicing rhetoric in blogging, too.

I've won the relationship lottery, I really have. In a city of 5.5 million people, in the third country I've lived in, I found someone who exemplifies the saying: When the going gets tough, the tough hit the books.

(edited for clarity)