Things I value unequally

Posted: - Modified:I was talking to someone who taught a class at Trade School Toronto. To enable more people to access education, the school has a barter system where instructors can post a list of things they value, and students can creatively pay for their education that way instead.

I’ve been thinking about this because a few friends have asked me for help with learning things, and because I’d like to offer pair programming like the way that Avdi does. But I know that people’s budgets can be a little tight, and just using money ignores a whole range of possibilities. What would my swap list be? Here are some of the things I value and would be willing to swap for:

- Money is useful because it can be translated into other things. It’s good to exchange money, because we get to practise agreeing on value. But if you have more time than money, or you have other things that we unequally value, let’s figure out how we can swap those instead.

- Notes: Share what you’re learning!

- Conversations over meals, particularly home-cooked ones; we need more leisurely conversations about life

- Questions – I want to write about useful ideas, so people’s questions are great for this

- Tools and processes. This includes software, and it also includes getting better at configuring or working with the tools I have. I’m particularly interested in:

- tools for tracking

- tools for connecting with people

- the Adobe Creative Suite of tools: how can I build a sketchnoting workflow around Illustrator?

- Skills

- Book-keeping, accounting, and personal finance planning – I would definitely love to ask someone book-keeping and accounting questions, especially regarding Canada

- Data visualization – bouncing ideas around, learning how to use tools like R and D3

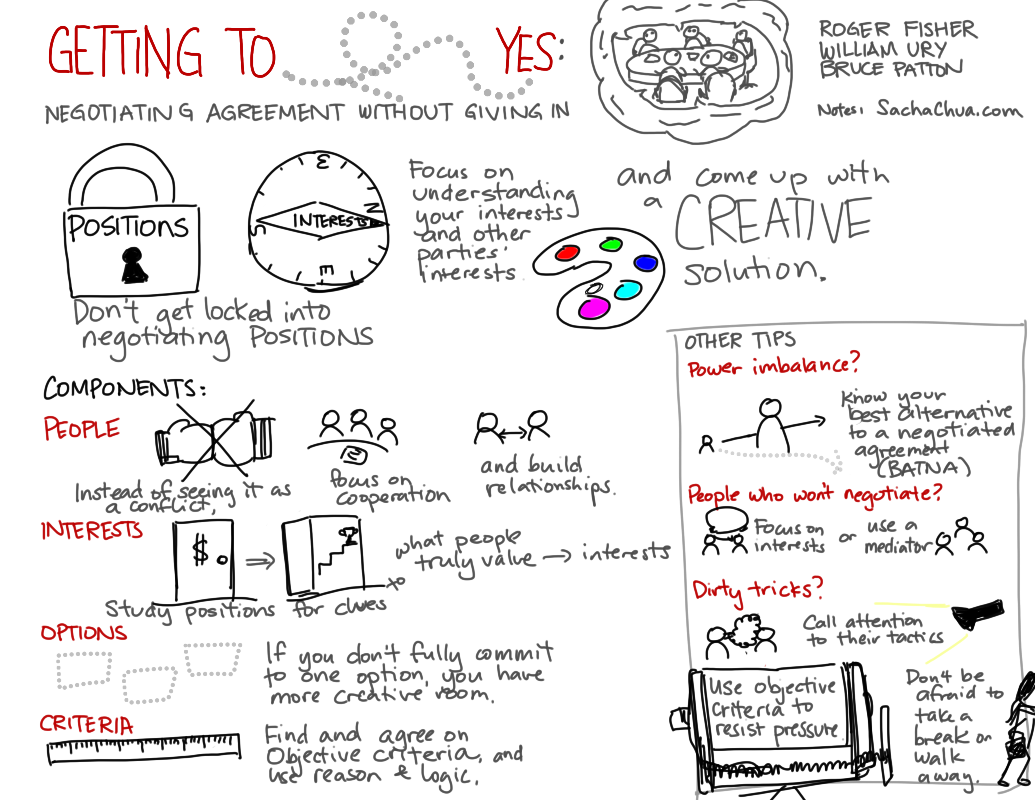

- Sketchnoting and graphic recording – help me broaden my visual vocabulary

- Delegation – talk to me about your processes

- Development – I’d love to learn more about Android, Rails, JQuery / Javascript, CSS, AutoHotkey, and other cool things

- Cooking – in person? it would be interesting to swap dishes or set up a potluck club

- Tell me what you’re good at, and chances are we can find some way to use that. I’m learning more about delegation and making things happen, so I’d love to learn how to work with all sorts of skills.

- Books

- Particularly business and communication books that aren’t carried by the Toronto Public Library; also, well-written children’s literature

- Book notes are useful, too!

- Time, chores, convenience: Groceries? Cat sitting? Hauling lots of books back and forth from the library?

There’s more we can add to this list, of course, so feel free to suggest something that you think might be a good fit.