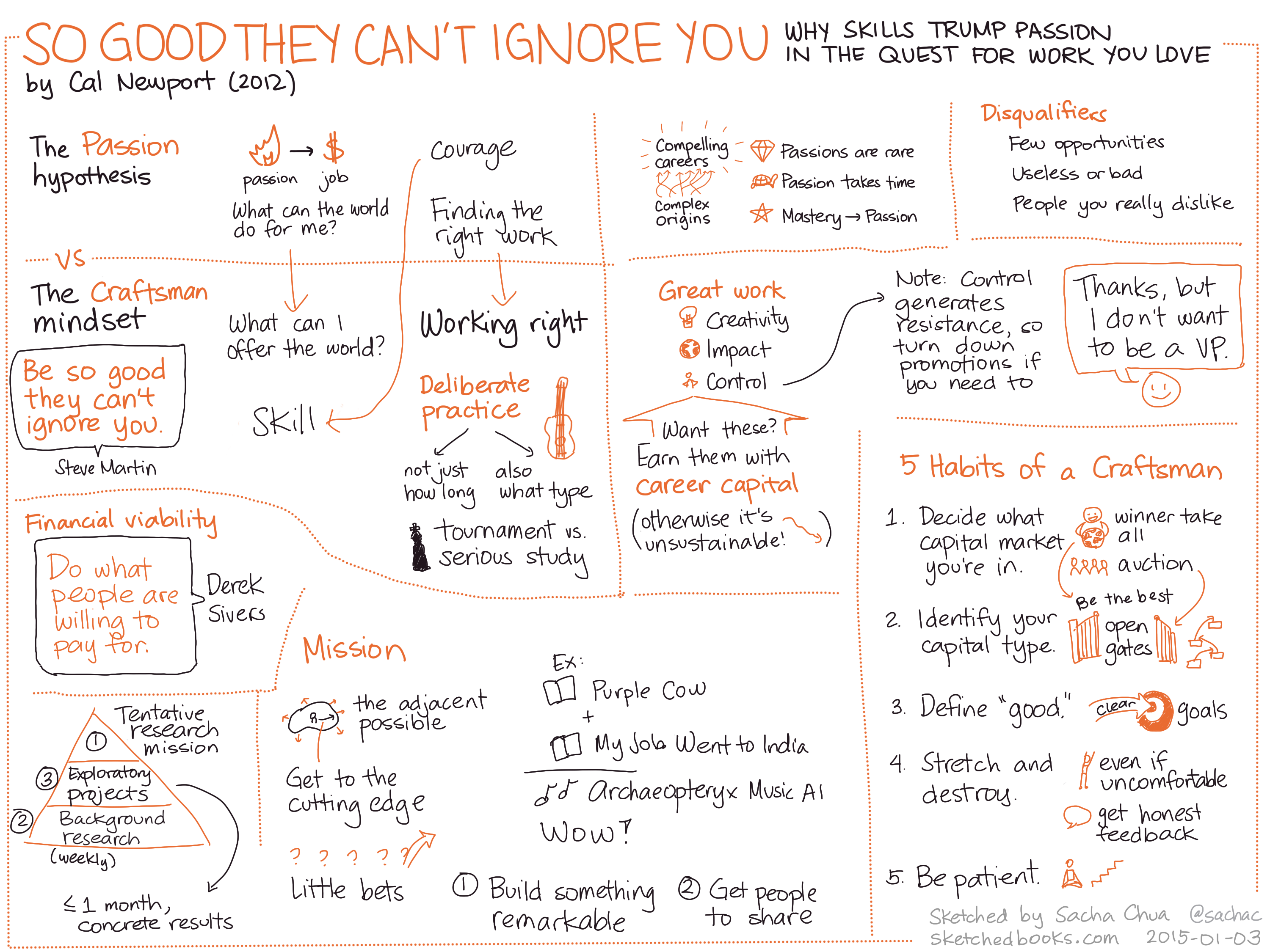

Visual book notes: So Good They Can’t Ignore You: Why Skills Trump Passion in the Quest for Work You Love – Cal Newport

Posted: - Modified: | career, visual-book-notesIt seems almost given that you should follow your passion, but what if you don’t know what that is? Or what if following your passion prematurely can lead to failure?

In So Good They Can’t Ignore You: Why Skills Trump Passion in the Quest for Work You Love (2012), Cal Newport gives more practical advice: Instead of jumping into a completely unknown field to follow a passion which might turn out to be imaginary, look for ways to translate or grow your existing capabilities. Develop a craftsman’s mindset so that you can improve through deliberate practice. Often it’s not a lack of courage that holds you back, but a lack of skill. As you build career capital, you can develop your appreciation of a field, possibly leading to a clear passion or a mission. You also can make little bets that help you move closer to the cutting edge so that you can make something remarkable. This qualifies you to do greater work that involves creativity, positive impact, and good control.

I’ve sketched the key points of the book below to make it easier to remember and share. Click on the image for a larger version that you can print if you want.

I agree with many of the ideas in the book, although I’m not entirely sure about the dichotomy that Newport sets up between passion and craftsmanship. Many of the passion-oriented books I’ve read encourage you to try out your ideas before making major changes to your life – for example, by working on your own business on weekends or by taking a second job. Very few people advocate leaping into the unknown, and if they do, they recommend having plenty of savings and a network of mentors, potential clients, and supporters. So the book comes down a little harshly on a caricature of the other side rather than the strongest form of the opposing side’s argument.

Amusingly enough, although the book describes What Color is Your Parachute as “the birth of the passion hypothesis”, I remember coming across the idea of gradually transitioning to a new field by first exploring something more related to your current one in What Color is Your Parachute, which recommends it as a way of lowering risk and clarifying what you want. I also remember the What Color is Your Parachute book to be less about impulsively following your whims and more about identifying and exploring the skills that gave you feelings of accomplishment.

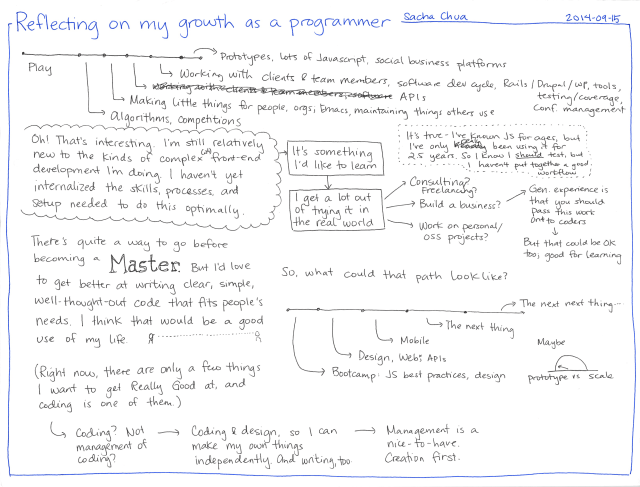

Anyway, I think you start with curiosity. Then you develop a little skill. This makes you more curious, which helps you learn more, and so on. That–combined with feedback and appreciation–helps fan a spark of interest into a flame. So it’s not really that you start with passion or that you spend many years developing your craft before you can enjoy it, but rather that you gradually figure out both. (I have a feeling this somewhat agrees with what the book would’ve been if it weren’t trying so hard to distinguish itself from advice about passion.)

We just don’t normally express ourselves that way, I guess. It’s almost as if people are expected to either have strong convictions about their life’s work, or to be lost at sea. If you say, “I’m still figuring things out,” it’s like you’re a drifter. If you say, “I’m not passionate about my work right now,” it’s like you’re just going through the motions. I don’t agree with this, which is why I like the book’s emphasis on forming hypotheses about what you want to do, and testing that with little bets that also develop your skills. (This is particularly apropos, since J- will be choosing a university or college course soon.)

Anyway, after reading this book, the specific take-away I’m looking forward to following up on is that of exploring adjacent possibilities more systematically. How can I move closer to the edge of discovery in myself and in the fields I’m interested in, and what new areas have been opened up? I’ve been thinking about designing more focused projects that result in things I can measure and share. That’s similar to the middle layer of the pyramid that Newport suggests:

- Tentative research mission – figuring out what you want

- One-month exploratory projects with concrete results

- Background results

On the whole, the book has a good message. You don’t have to love something to get good at it. Sometimes (often?) getting good at something will help you like it or even love it.

But the book feels a little… uneven, I guess? The anecdotes feel like they’re making too-similar points. The ones about failure feel unsympathetic and hand-picked for straw-man arguments. I imagine most businesses are not started out of the blue because of some grand passion. People prepare, they minimize risk, they work hard. Passion for something – either the work, the customers, or even just the life that’s afforded by the work – pulls them through the toughest parts and keeps them going. Sometimes they succeed for reasons unrelated to their skills; sometimes they fail for reasons unrelated to their passions. Sometimes things just happen. There are everyday businesses that don’t have the creativity, grand positive impact, or full control that are idealized in the book, but that still give people enjoyable lives. I think that the techniques and ingredients described by Newport in his book are good, but they are not essential to an awesome life.

On a somewhat related note, in the past few years, I’ve been learning to let go of the desire for either passion or mastery, Instead, I’m embracing uncertainty and beginner-ness, setting aside time for things I don’t quite love yet. It’s a challenging path, but it tickles my brain. =)

Anyway, if you’re looking for a counterpoint to the usual “Follow your passion!” advice and you want to check out So Good They Can’t Ignore You, you can check out this book.

Enjoy!