Learning more about looking ahead together

| parenting, planning

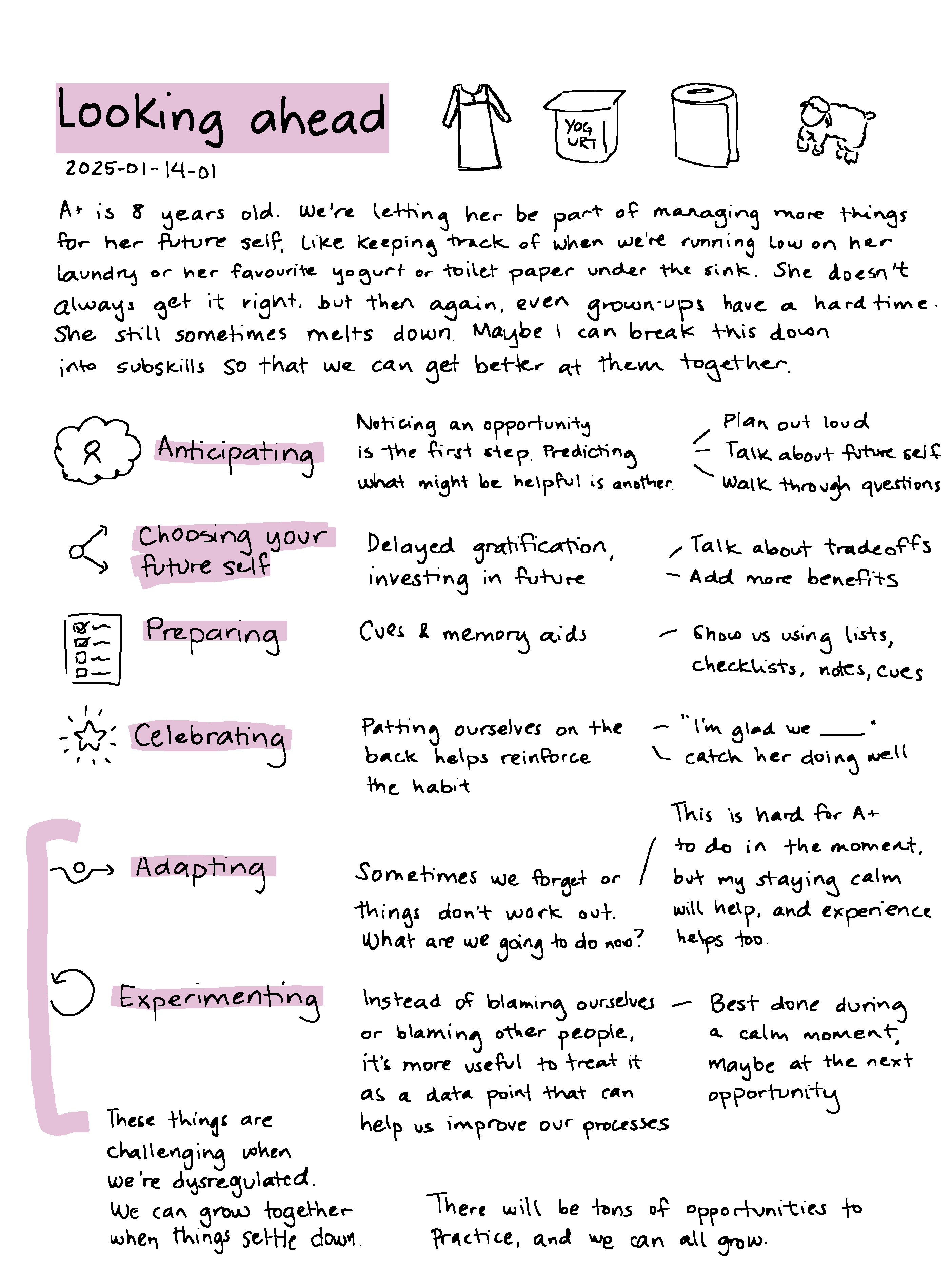

Text from sketch

A+ is 8 years old. We're letting her be part of managing more things for her future self, like keeping track of when we're running low on her laundry or her favourite yogurt or toilet paper under the sink. She doesn't always get it right, but then again, even grown-ups have a hard time. She still sometimes melts down. Maybe I can break this down into subskills so that we can get better at them together.

- Anticipating: Noticing an opportunity is the first step. Predicting what might be helpful is another.

- Plan out loud

- Talk about future self

- Walk through questions.

- Choosing your future self: Delayed gratification, investing in future

- Talk about tradeoffs

- Add more benefits

- Preparing: Cues & memory aids

- Show us using lists, checklists, notes, cues

- Celebrating: Patting ourselves on the back helps reinforce the habit

- "I'm glad we…"

- catch her doing well

- Adapting: Sometimes we forget or things don't work out. What are we going to do now?

- This is hard for A+ to do in the moment, but my staying calm will help, and experience helps too.

- Experimenting: Instead of blaming ourselves or blaming other people, it's more useful to treat it as a data point that can help us improve our processes.

- Best done during a calm moment, maybe at the next opportunity

These things are challenging when we're dysregulated. We can grow together when things settle down.

There will be tons of opportunities to practice, and we can all grow.

One of the neat things about parenting is that I get to think about how to develop different skills. Today I want to think about planning ahead. I can see the beginnings of it developing in A+, like when she says, "I'm going to put on my boots before I put on my mittens because that's easier when you have fingers." I can see when it's more of a struggle, like when we've forgotten to bring the stuffed toy she wanted to take along and she's overwhelmed with frustration. I can draw parallels between that and the way I'm learning more about this skill myself, like when we use the Band-aids I've stashed in my emergency kit or when I've forgotten to pack lunch and have to find something that A+ will like within walking distance. Even grown-ups have a hard time with these skills. We've got plenty of examples around us of people working on improving that skill and people who struggle.

I like breaking skills down into smaller chunks so that they're easier to think about, practise, and learn. Breaking down the idea of looking ahead into anticipating, choosing your future self, preparing, celebrating, adapting, and experimenting makes more sense to me than treating it as one big lump. I want to think about these subskills in this blog post so that I can get better at them and so that we can swap notes.

The parts that are hardest for A+ at the moment are adapting and experimenting. That makes a lot of sense. That's when planning gets tested. That's when you get feedback from reality. That's difficult for lots of people, even grown-ups, and I have plenty to learn about those parts myself.

Adapting: cognitive flexibility

I think of adapting as handling things in the moment, switching to the question, "So, what are we going to do now?" To be able to do that, A+ needs to be able to manage or sidestep the fight-flight-freeze response. I think a large part of this might just be accumulating enough experiences to know that these things are survivable, and part of it is probably waiting for her brain to mature. I can't skip those things for her, but I can validate her feelings and show her that they're tolerable by staying calm myself. I'm pretty good at staying calm if I've paid attention to my basic needs. If I'm off-balance, I can ask W- for help. When I'm calm, I can be curious about what she feels and how she eventually calms down.

I also find this part challenging. When she asks me for something that she's thought of late, sometimes I'm not sure whether my figuring it out will mean she doesn't get as much practice or feedback in planning ahead or adapting. Sometimes I hesitate or say no, and then she gets grumpy and frustrated, and then I become even less flexible because I don't want to encourage grumping at me to get what she wants. I guess she's going to eventually figure out how and when to ask so that she has a higher likelihood of yes. For my part, I think it's okay to want most decisions to be slowed down and considered without pressure, so I can get better at tolerating A+'s discomfort so that she gets that feedback.

When it comes to accepting things, I like drawing on radical acceptance and Stoic philosophy, although A+'s probably a little young for me to talk about preferred and dispreferred indifferents, at least in those terms. I can model those ideas out loud, though.

Another part of adapting is having a wide vocabulary of ways we can solve problems, which we pick up through experience, skills, and learning from other people.

Sometimes I come up with ways to solve a problem, but she's not ready to move to that step yet because she's still dealing with strong feelings, and I can't help her co-regulate because she's grumpy with me. There's no rushing past that, there's no shortcut I can do to help her with her feelings, but I can be curious about what she does to eventually help herself cool down.

Besides, me coming up with ways to solve a problem is not nearly as useful as her eventually learning how to cool down and come up with her own ideas for solving it. I can save my ideas for wondering out loud, if she asks me for help. Might as well not waste a good motivating problem.

Resources:

- Helping Kids With Flexible Thinking - Child Mind Institute

- Validate emotions, get them involved, model flexibility, get help if needed

- Flexible Thinking: How to Help Kids Do It

- Validate emotions, involve them in decisions, give them reminders, model the behavior, provide cognitive flexibility exercises

- How to Develop Flexible Thinking | Parenting… | PBS KIDS for Parents

- This splits cognitive flexibility further into flexible thinking (thinking about a problem in a new way) and set shifting (letting go of an old way in order to try a new way).

- Self-talk, switching up routines, Amelia Bedelia, jokes

- Flexible Thinking in Children | Beyond BookSmart

- Breaks, flexible/divergent thinking games, switching up routines, self-talk

Experimenting: reflective practice

It would be counterproductive for me to try to cushion A+ from failure. I want her to develop her own skills, so I want her to make decisions (especially ones without long-term negative consequences). Some of those decisions won't work out the way she wanted them to, but that's life. Besides, "How can we make things better next time?" is a question that can build on both positive and negative experiences, so even the uncomfortable moments can be useful.

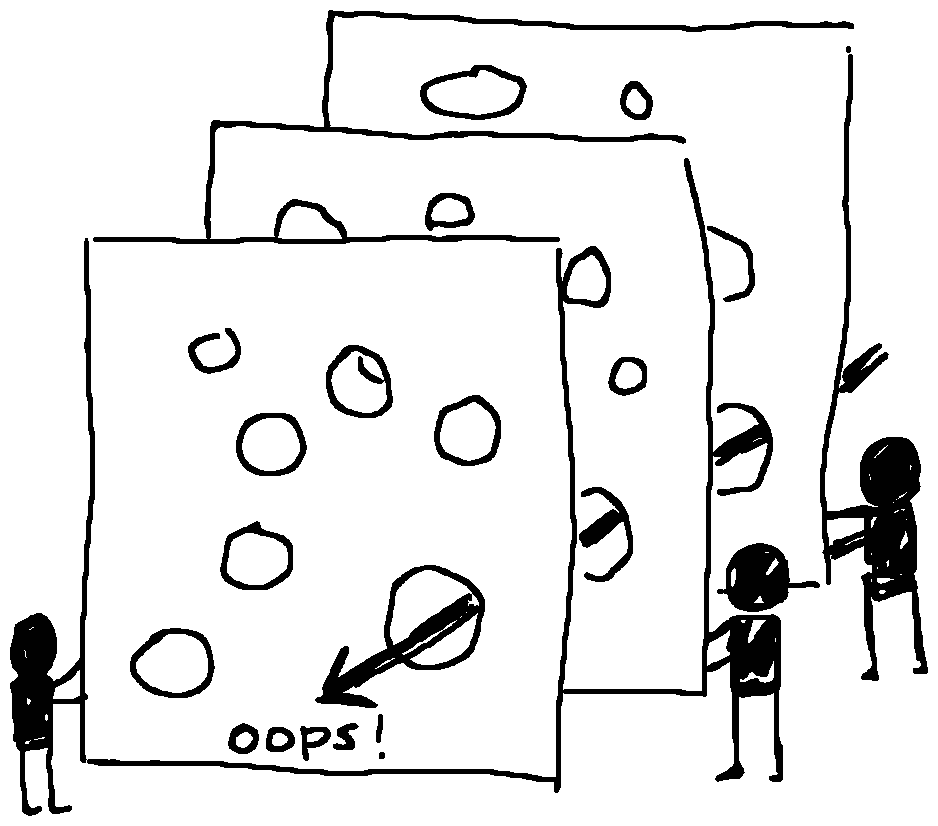

When things don't work out, it's very tempting to blame ourselves or other people, but that doesn't really help us more forward. I want to be able to see the ups and downs as data points in our experiments and as opportunities to improve our processes. I keep working on getting better at responding to my own oopses and my delegated oopses. Fortunately, I have lots of opportunities to practice.

From James Reason's Swiss Cheese model of human errors:

The basic premise in the system approach is that humans are fallible and errors are to be expected, even in the best organisations. Errors are seen as consequences rather than causes, having their origins not so much in the perversity of human nature as in “upstream” systemic factors. … When an adverse event occurs, the important issue is not who blundered, but how and why the defences failed.

Failures point to multiple ways that we might be able to learn and to improve our systems. Paying attention to those opportunities could save us from bigger mistakes later on. Finding bugs when developing means dealing with fewer bugs in production, and this is basically her development environment. Besides, there's a lot of satisfaction in improving our systems.

Still, it's hard to think when people are dysregulated. It's easier to take that perspective when things are calm and there's an opportunity to try something new. So in the moment, my job is to weather the storm and adapt as well as I can. After the storm passes, I can think about what would make things better next time around. When I notice that A+ is calm and ready to learn, I can invite her to think along with me. She still gets defensive if I use the past events as an anchor for reflection. She responds better if we're planning for something that's coming up soon. I can use avoidance sparingly ("last time, that didn't work out so well") and lean more on building on things that worked well. That kind of reflection will probably be mostly on my side for now, but maybe she'll grow into it eventually.

I keep a brief journal, but life with A+ doesn't usually lend itself to quickly looking things up so that I can pull in the appropriate anecdotes at the right time. The tough moments tend to be easy to remember because they're emotionally-laden, but since I want to build on positive experiences as well, I can:

- slow down and notice things out loud in the moment,

- retell it shortly after, perhaps during dinnertime,

- capture it in my journal so I can look it up again, and

- think of the next little step, or some cues or situations it might be relevant to.

It's also probably easier for A+ to learn from my thinking out loud about my own processes than about hers. Fortunately, life gives me plenty of opportunities to practise learning out loud.

We already have a habit around drawing a moment of the day, and I could probably add something like Rose-Thorn-Bud to dinnertime or bedtime conversations. A+'s teachers sometimes add reflection to their assignments, too.

I probably don't even have to worry too much about explicitly teaching A+ these skills. I just have to try to not get in the way of her learning them. If we learn together, I think we'll figure all sorts of cool things out.