Large documents are almost impossible to write without outlines. There’s just too much to fit in your head. Outlines help you work with a structure, so that you can see the big picture and how sections fit together. Outlines are also surprisingly useful when brainstorming. You can work with varying levels of detail, starting with a high-level overview and successively refining it, or starting with the details and then letting the structure emerge as you organize those details into groups.

Emacs has one of the most powerful outline editors I’ve come across. Although word processors like Microsoft Word and OpenOffice.org Writer support outlines too, Emacs has a gazillion keyboard shortcuts, and once you get the hang of them, you’ll want them in other applications as well. In addition, working in Emacs tends to force you to focus on the content instead of spending time fiddling with the formatting. Whether you’re writing personal notes or working on a document that’s due tomorrow, this is a good thing.

In this section, you’ll learn how to outline a document using Org. You’ll be able to create headings, sub-headings, and text notes. You’ll also learn how to manage outline items by promoting, demoting, and rearranging them.

Understanding Org

Org is primarily a personal information manager that keeps track of your tasks and schedule, and you’ll learn more about those features in chapters 8 and 9. However, Org also has powerful outline-management tools, which is why I recommend it to people who want to write and organize outlined notes.

The structure of an Org file is simple: a plain text file with headlines, text, and some additional information such as tags and timestamps. A headline is any line that stars with a series of asterisks. The more asterisks there are, the deeper the headline is. A second-level headline is the child of the first-level headline before it, and so on. For example:

* This is a first-level headline

Some text under that headline

** This is a second-level headline

Some more text here

*** This is a third-level headline

*** This is another third-level headline

** This is a second-level headline

Because Org uses plain text, it’s easy to back up or process using scripts. Org’s sophistication comes from keyboard shortcuts that allow you to quickly manipulate headlines, hide and show outline subtrees, and search for information.

GNU Emacs 22 includes Org. To automatically enable Org mode for all files with the .org extension, add the following to your ~/.emacs:

(require 'org)

(add-to-list 'auto-mode-alist '("\\.org$" . org-mode))

To change to org-mode manually, use M-x org-mode while viewing a file. To enable Org on a per-file basis, add

-*- mode: org -*-

to the first line of the files that you would like to associate with Org.

Working with Outlines

You can keep your notes in more than one Org file, but let’s start by creating ~/notes.org. Open ~/notes.org, which will automatically be associated with Org Mode. Type in the general structure of your document. You can type in something like this:

* Introduction

* ...

You can also use M-RET (org-meta-return) to create a new headline at the same level as the one above it, or a first-level headline if the document doesn’t have headlines yet.

Create different sections for your work. For example, a thesis might be divided into introduction, review of related literature, description of study, methodology, results and analysis, and conclusions and recommendations. You can type in the starting asterisks yourself, or you can use M-RET (org-meta-return) to create headings one after the other.

Now that you have the basic structure, start refining it. Go to the first section and use a command like C-o (open-line) to create blank space. Add another headline, but this time, make it a second-level headline under the first. You can do that by either typing in two asterisks or by using M-RET (org-meta-return, which calls org-insert-heading) and then M-right (org-metaright, which calls org-do-demote). Then use M-RET (org-meta-return; org-insert-heading) for the other items, or type them in yourself. Repeat this for other sections, and go into as much detail as you want.

What if you want to reorganize your outline? For example, what if you realized you’d accidentally put your conclusions before the introduction? You could either cut and paste it using Emacs shortcuts, or you can use Org’s outline management functions. The following keyboard shortcuts are handy:

| Action |

Command |

Shortcut |

Alternative |

| Move a subtree up |

org-metaup / org-move-subtree-up |

M-up |

C-c C-x u |

| Move a subtree down |

org-metadown / org-move-subtree-down |

M-down |

C-c C-x d |

| Demote a subtree |

org-shiftmetaright / org-demote-subtree |

S-M-right |

C-c C-x r |

| Promote a subtree |

org-shiftmetaleft / org-promote-subtree |

S-M-left |

C-c C-x l |

| Demote a headline |

org-metaright / org-do-demote |

M-right |

C-c C-x <right> |

| Promote a headline |

org-metaleft / org-do-promote |

M-left |

C-c C-x <left> |

| Collapse or expand a subtree |

org-cycle (while on headline) |

TAB |

|

| Collapse or expand everything |

org-shifttab (org-cycle) |

S-TAB |

C-u TAB |

Use these commands to help you reorganize your outline as you create a skeleton for your document. These commands make it easy to change your mind about the content or order of sections. You might find it easier to sketch a rough outline first, then gradually fill in more and more detail. On the other hand, you might find it easier to pick one section and keep drilling it down until you have headlines some seven levels deep. When you reach that point, all you need to do is add punctuation and words like "and" or "but" between every other outline item, and you’re done!

Well, no, not likely. You’ll probably get stuck somewhere, so here are some tips for keeping yourself going when you’re working on a large document in Org: brainstorming and getting a sense of your progress.

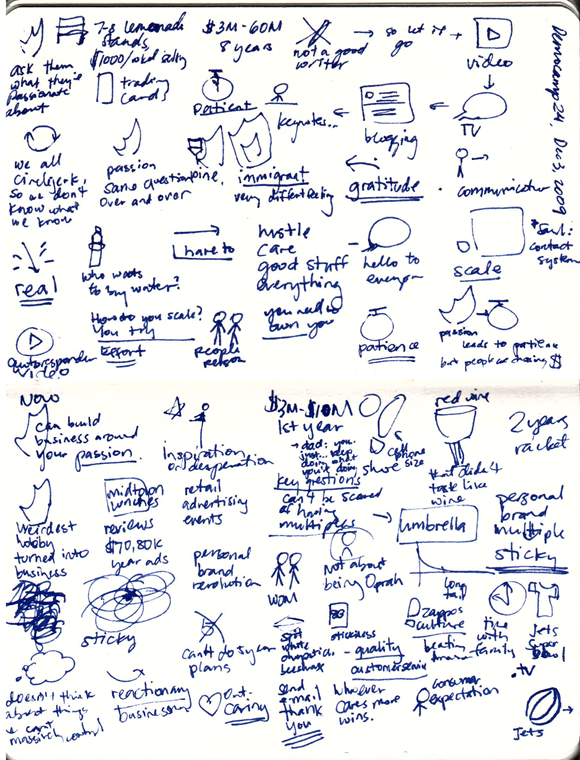

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is a great way to break your writer’s block or to generate lots of possibilities. The key idea is to come up with as many ideas as you can, and write them all down before you start evaluating them.

I usually switch to paper for mindmapping and brainstorming because paper helps me think in a more colorful and non-linear way. However, it can be hard to manage large mindmaps on paper, because you can’t reorganize nodes easily. Despite its text-heavy interface, Org is one of the best mindmapping tools I’ve come across. Because it’s built into Emacs, everything can be done through keyboard shortcuts.

When you’re brainstorming, you might like working from two different directions. Sometimes it’s easier to start with an outline and to add more and more detail. Other times, you may want to jot quick ideas and then organize them into groups that make sense. Org provides support for both ways of working.

Brainstorming bottom-up is similar to David Allen’s Getting Things Done method in that separating collection from organization is a good idea. That is, get the ideas out of your head first before you spend time trying to figure out the best way to organize them. To get things out of your head quickly, collect your ideas by using the M-RET (org-meta-return) to create a new heading, typing in your idea, and using M-RET (org-meta-return) to create the next heading. Do this as many times as needed.

One way to encourage yourself to brainstorm lots of ideas is to give yourself a quota. Charles Cave described this technique in an article on org-mode, and it’s a great way to use structure to prompt creativity. Simply start by adding a number of empty headings (say, 20), then work towards filling that quota. For example, you might start with ten blanks for ideas, then gradually fill them in like this:

* Things that make me happy

** Curling up with a good book

** Watching a brilliant sunset

** Giving or getting a big warm hug

** Writing a cool piece of Emacs code

**

**

**

**

**

**

When all of your ideas are in Org, start organizing them. This is where you move ideas around using M-S-up (org-shiftmetaup) and M-S-down (org-shift-metadown), which call org-move-subtree-up and org-move-subtree-down. This is also a good time to use headings to group things together.

Getting a Sense of Progress

You’ve brainstormed. You’ve started writing your notes. And if you’re working on a large document, you might lose steam at some point along the way. For example, while working on this book, I often find myself intimidated by just how much there is to write about Emacs. It helps to have a sense of progress such as the number of words written or the number of sections completed. To see a word count that updates every second, add this code to your ~/.emacs:

(defvar count-words-buffer

nil

"*Number of words in the buffer.")

(defun wicked/update-wc ()

(interactive)

(setq count-words-buffer (number-to-string (count-words-buffer)))

(force-mode-line-update))

; only setup timer once

(unless count-words-buffer

;; seed count-words-paragraph

;; create timer to keep count-words-paragraph updated

(run-with-idle-timer 1 t 'wicked/update-wc))

;; add count words paragraph the mode line

(unless (memq 'count-words-buffer global-mode-string)

(add-to-list 'global-mode-string "words: " t)

(add-to-list 'global-mode-string 'count-words-buffer t))

;; count number of words in current paragraph

(defun count-words-buffer ()

"Count the number of words in the current paragraph."

(interactive)

(save-excursion

(goto-char (point-min))

(let ((count 0))

(while (not (eobp))

(forward-word 1)

(setq count (1+ count)))

count)))

The best way I’ve found to track my progress in terms of sections is to use a checklist. For example, the collapsed view for this section looks like this:

** Outline Notes with Org [7/9] ;; (1)

*** [X] Outlining Your Notes... ;; (2)

*** [X] Understanding Org...

*** [X] Working with Outlines...

*** [X] Brainstorming...

*** [ ] Getting a Sense of Progress... ;; (3)

*** [X] Searching Your Notes...

*** [X] Hyperlinks...

*** [X] Publishing Your Notes...

*** [ ] Integrating Remember with Org

- (1): [7/9] shows that I’ve completed 7 of 9 parts.

- (2): [X] indicates finished parts.

- (3): [ ] indicates parts I still need to do.

This is based on the checklist feature in Org. However, the standard feature works only with lists like this:

*** Items [1/3]

- [X] Item 1

- [ ] Item 2

- [ ] Item 3

Add the following code to your ~/.emacs in order to make the function work with headlines:

(defun wicked/org-update-checkbox-count (&optional all)

"Update the checkbox statistics in the current section.

This will find all statistic cookies like [57%] and [6/12] and update

them with the current numbers. With optional prefix argument ALL,

do this for the whole buffer."

(interactive "P")

(save-excursion

(let* ((buffer-invisibility-spec (org-inhibit-invisibility))

(beg (condition-case nil

(progn (outline-back-to-heading) (point))

(error (point-min))))

(end (move-marker

(make-marker)

(progn (or (outline-get-next-sibling) ;; (1)

(goto-char (point-max)))

(point))))

(re "\\(\\[[0-9]*%\\]\\)\\|\\(\\[[0-9]*/[0-9]*\\]\\)")

(re-box

"^[ \t]*\\(*+\\|[-+*]\\|[0-9]+[.)]\\) +\\(\\[[- X]\\]\\)")

b1 e1 f1 c-on c-off lim (cstat 0))

(when all

(goto-char (point-min))

(or (outline-get-next-sibling) (goto-char (point-max))) ;; (2)

(setq beg (point) end (point-max)))

(goto-char beg)

(while (re-search-forward re end t)

(setq cstat (1+ cstat)

b1 (match-beginning 0)

e1 (match-end 0)

f1 (match-beginning 1)

lim (cond

((org-on-heading-p)

(or (outline-get-next-sibling) ;; (3)

(goto-char (point-max)))

(point))

((org-at-item-p) (org-end-of-item) (point))

(t nil))

c-on 0 c-off 0)

(goto-char e1)

(when lim

(while (re-search-forward re-box lim t)

(if (member (match-string 2) '("[ ]" "[-]"))

(setq c-off (1+ c-off))

(setq c-on (1+ c-on))))

(goto-char b1)

(insert (if f1

(format "[%d%%]" (/ (* 100 c-on)

(max 1 (+ c-on c-off))))

(format "[%d/%d]" c-on (+ c-on c-off))))

(and (looking-at "\\[.*?\\]")

(replace-match ""))))

(when (interactive-p)

(message "Checkbox statistics updated %s (%d places)"

(if all "in entire file" "in current outline entry")

cstat)))))

(defadvice org-update-checkbox-count (around wicked activate)

"Fix the built-in checkbox count to understand headlines."

(setq ad-return-value

(wicked/org-update-checkbox-count (ad-get-arg 1))))

Now add [ ] or [X] to the lower-level headlines you want to track. Add [/] to the end of the higher-level headline containing those headlines. Type C-c # (org-update-checkbox-count) to update the count for the current headline, or C-u C-c C-# (org-update-checkbox-count) to update all checkbox counts in the whole buffer.

If you want to see the percentage of completed items, use [%] instead of [/]. I find 7/9 to be easier to understand than 71%, but fractions might work better for other cases.

Okay, you’ve written a lot. How do you find information again?

Searching Your Notes

When you’re writing your notes, you might need to refer to something you’ve written. You may find it helpful to split your screen in two with C-x 3 (split-window-horizontally) or C-x 2 (split-window-vertically). To switch to another window, type C-x o (other-window) or click on the window. To return to just one window, use C-x 1 (delete-other-windows) to focus on just the current window, or C-x 0 (delete-window) to get rid of the current window.

Now that you’ve split your screen, how do you quickly search through your notes? C-s (isearch-forward) and C-r (isearch-backward) are two of the most useful Emacs keyboard shortcuts you’ll ever learn. Use them to not only interactively search your Org file, but also to quickly jump to sections. For example, I often search for headlines by typing * and the first word. Org searches collapsed sections, so you don’t need to open everything before searching.

To search using Org’s outline structure, use C-c / r (org-sparse-tree, regexp), which will show only entries matching a regular expression. For more information about regular expressions, read the Emacs info manual entry on Regexps. Here are a few examples:

| To find |

Search for |

| All entries containing "cat" |

cat |

| All entries that contain "cat" as a word by itself (example: "cat," but not "catch") |

\<cat\> |

| All entries that contain 2006, 2007, or 2008 |

200[678] |

Hyperlinks

If you find yourself frequently searching for some sections, you might want to create hyperlinks to them. For example, if you’re using one file for all of your project notes instead of splitting it up into one file per project, then you probably want a list of projects at the beginning of the file so that you can jump to each project quickly.

You can also use hyperlinks to keep track of your current working position. For example, if you’re working on a long document and you want to keep your place, create a link anchor like <<TODO>> at the point where you’re editing, and add a link like [[TODO]] at the beginning of your file.

You can create a hyperlink to a text search by putting the keywords between two pairs of square brackets, like this:

See [[things that make me happy]]

You can open the link by moving the point to the link and typing C-c C-o (org-open-at-point). You can also click on the link to open it. Org will then search for text matching the query. If Org doesn’t find an exact match, it tries to match similar text, such as "Things that make me really really happy".

If you find that the link does not go where you want it to go, you can limit the text search. For example, if you want to link to a headline and you know the headline will be unique, you can add an asterisk at the beginning of the link text in order to limit the search to headlines. For example, given the following text:

In this file, I'll write notes on the things that make me happy. (1)

If I ever need a spot of cheering up, I'll know just what to do!

** Things that make me happy (2)

*** ...

Example

Link 1: [[things that make me happy]]

Link 2: [[*things that make me happy]]

Link 1 would lead to (1), and Link 2 would lead to (2).

To define a link anchor, put the text in double angled brackets like this:

<<things that make me happy>>

A link like [[things that make me happy]] would then link to that instead of other occurances of the text.

You can define keywords that will be automatically hyperlinked throughout the file by using radio targets. For example, if you’re writing a jargon-filled document and you frequently need to refer to the definitions, it may help to make a glossary of terms such as "regexp" and "radio target", and then define them in a glossary section at the end of the file, like this:

*** glossary

<<<radio target>>> A word or phrase that is automatically hyperlinked whenever it appears.

<<<regexp>>> A regular expression. See the Emacs info manual.

Radio targets are automatically enabled when an Org file is opened in Emacs. If you’ve just added a radio target, enable it by moving the point to the anchor and pressing C-c C-c (org-ctrl-c-ctrl-c). This turns all instances of the text into hyperlinks that point to the radio target.

Publishing Your Notes

You can keep your notes as a plain text file, or you can publish them as HTML or LaTeX. HTML seems to be the easiest way to let non-Emacs users read your notes, as a large text file without pretty colors can be hard to read.

To export a file to any of the formats that Org understands by default, type C-c C-e (org-export). You can then type ‘h’ (org-export-as-html) to export it as HTML for websites. You can also type ‘l’ (org-export-as-latex) to export it to LaTeX, a scientific typesetting language, which can then be published as PDF or PS. Another way to convert it to PDF is to export it as HTML, open it in OpenOffice.org Writer, and use the Export to PDF feature. You can also open HTML documents in other popular word processors to convert them to other supported formats.

By default, Org exports all the content in the current file. To limit it only to the visible content, use C-c C-e v (org-export-visible) followed by either ‘h’ for HTML or ‘l’ for LaTeX.

If you share your notes, you may want to export an HTML version every time you save an Org file. Here is a quick and dirty way to publish all Org files to HTML every time you save them:

(defun wicked/org-publish-files-maybe ()

"Publish this file."

(org-export-as-html-batch)

nil)

(add-hook 'org-mode-hook ;; (1)

(lambda ()

(add-hook (make-local-variable 'after-save-hook) ;; (2)

'wicked/org-publish-files-maybe)))

(Update: Feb 22 2011: Thanks to Neilen for the fix!)

- (1) Every time a buffer is set to Org mode…

- (2) Add a function that publishes the file every time that file is saved.

What if most of your files are private, but you want to publish only a few of them? To control this, let’s add a new special keyword "#+PUBLISH" to the beginning of the files that you want to be automatically published. Replace the previous code in your ~/.emacs with this:

(defun wicked/org-publish-files-maybe ()

"Publish this file if it contains the #+PUBLISH: keyword"

(save-excursion

(save-restriction

(widen)

(goto-char (point-min))

(when (re-search-forward

"^#?[ \t]*\\+\\(PUBLISH\\)"

nil t)

(org-export-as-html-batch)

nil))))

(add-hook 'org-mode-hook

(lambda ()

(add-hook (make-local-variable 'after-save-hook)

'wicked/org-publish-files-maybe)))

and add #+PUBLISH on a line by itself to your ~/notes.org file, like this:

#+PUBLISH

* Things that make me happy

When you save any Org file that contains the keyword, the corresponding HTML page will also be created. You can then use a program like rsync or scp to copy the file to a webserver, or you can copy it to a shared directory.

Integrating Remember with Org

You can use Remember to collect notes that you will later integrate into your outline. Add the following code to your ~/.emacs to set it up:

(global-set-key (kbd "C-c r") 'remember) ;; (1)

(add-hook 'remember-mode-hook 'org-remember-apply-template) ;; (2)

(setq org-remember-templates

'((?n "* %U %?\n\n %i\n %a" "~/notes.org"))) ;; (3)

(setq remember-annotation-functions '(org-remember-annotation)) ;; (4)

(setq remember-handler-functions '(org-remember-handler)) ;; (5)

- 1: Handy keyboard shortcut for (r)emember

- 2: Creates a template for (n)otes

- 3: Create a note template which saves the note to ~/notes.org, or whichever Org file you want to use

- 4: Creates org-compatible context links

- 5: Saves remembered notes to an Org file

With this code, you can type C-c r n (remember, Notes template) to pop up a buffer (usually containing a link to whatever you were looking at), write your note, and type C-c C-c (remember-buffer) to save the note and close the buffer.

You can use this to store snippets in your notes file, or to quickly capture an idea that comes up when you’re doing something else.

Now you know how to sketch an outline, reorganize it, fill it in, brainstorm, stay motivated, and publish your notes. I look forward to reading what you have to share!