The book that got me into Stoic thinking was William Irvine’s A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy (2009). Stoicism resonated with me: the reminder that my perception of things is separate from what those things are; the acceptance that I can control only how I respond to life, not what happens; the awareness of mortality that belies the insignificance of our drama and sharpens the appreciation of our short lives.

When I went through popular translations of the source books like the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius and Epictetus’ Discourses and the Enchiridion, I found them easy to read, with a wealth of ideas to apply to my life. Since then, I’ve been on the lookout for more applications of Stoicism to everyday life. Naturally, Ryan Holiday’s The Obstacle Is The Way: The Timeless Art of Turning Trials into Triumph (2014) crossed my radar.

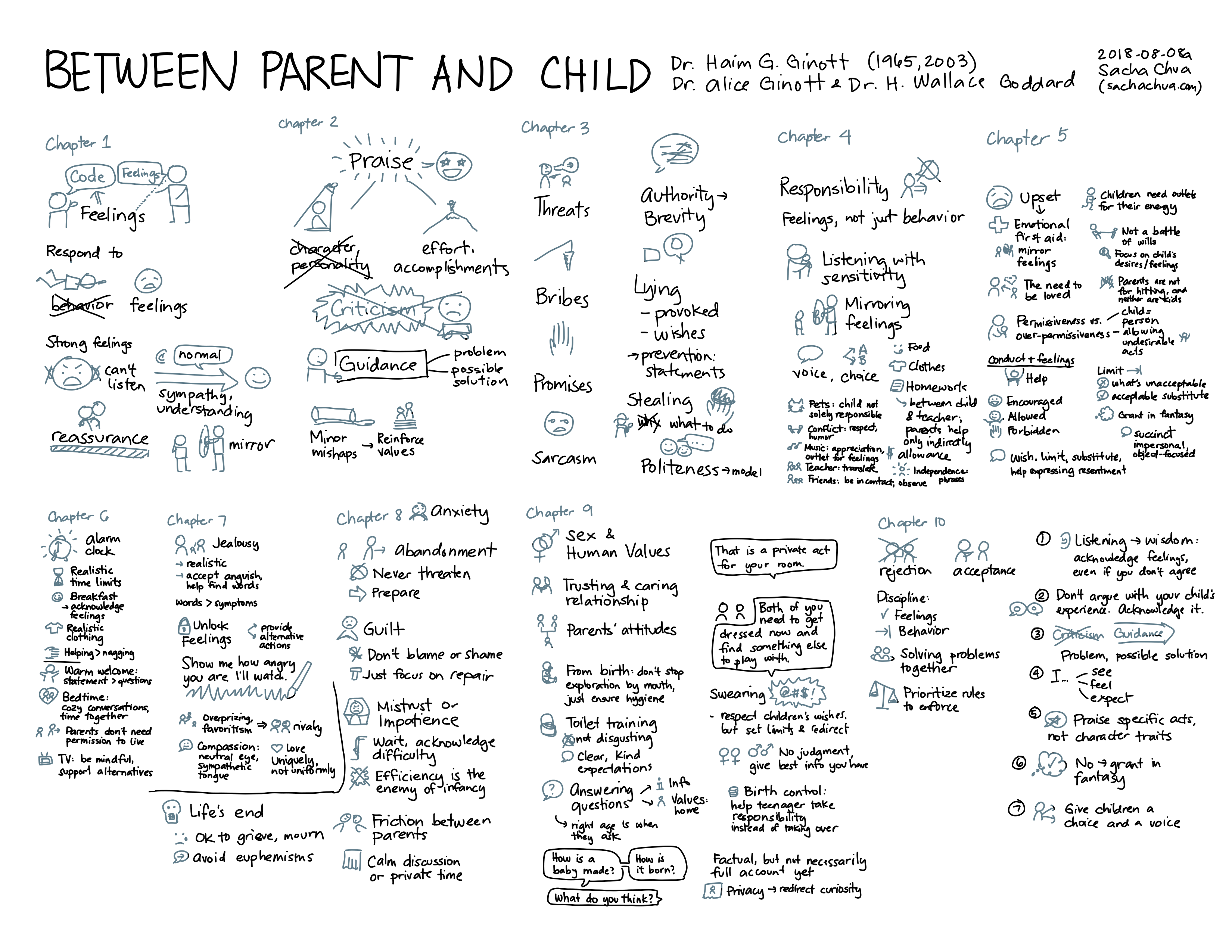

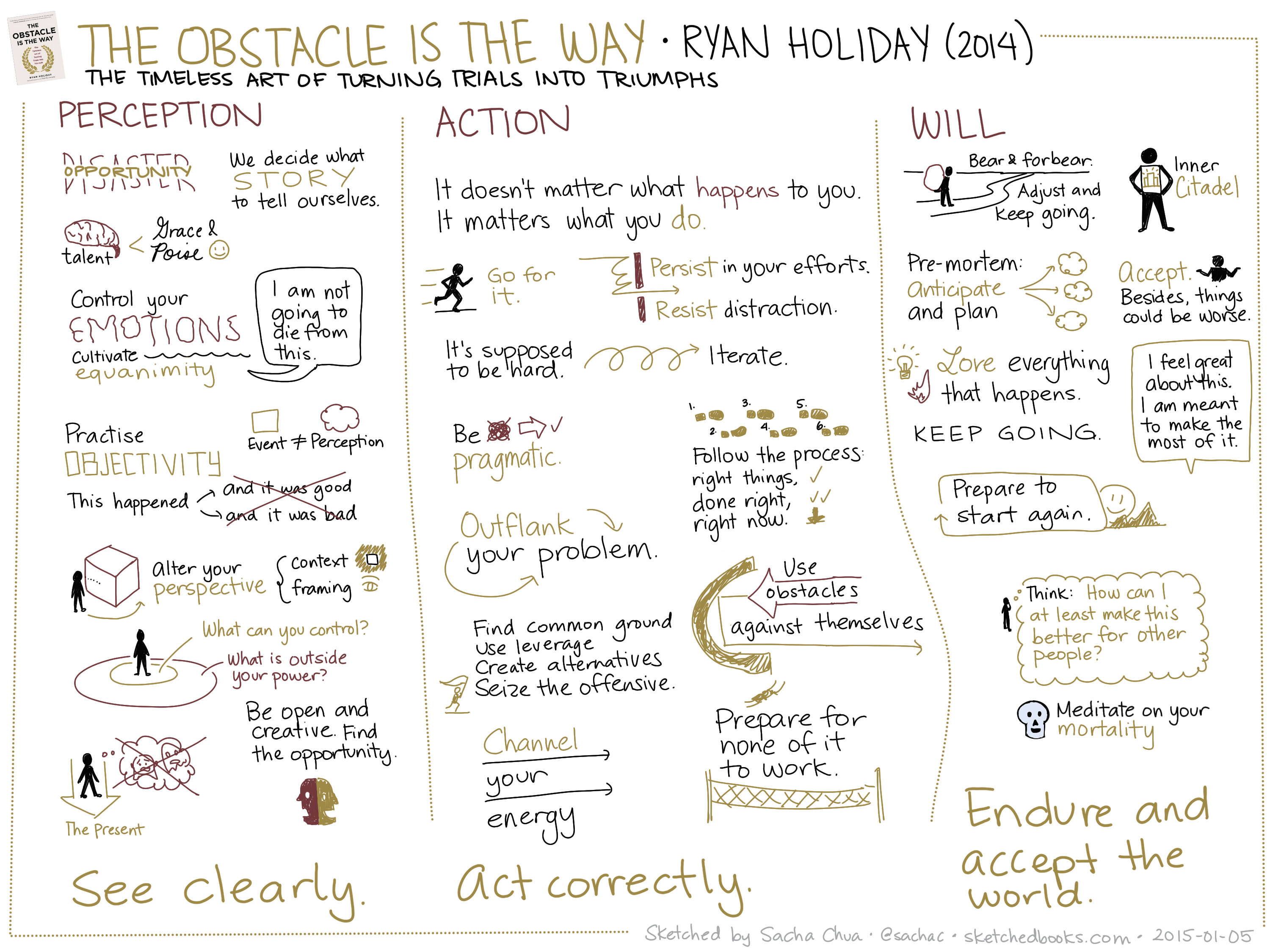

The book expands on the idea that you can view obstacles as opportunities, taking advantage of them in order to grow. Almost all of the thirty-two chapters (covering aspects of perception, action, and will) are illustrated with an anecdote or two, followed by some questions and advice.

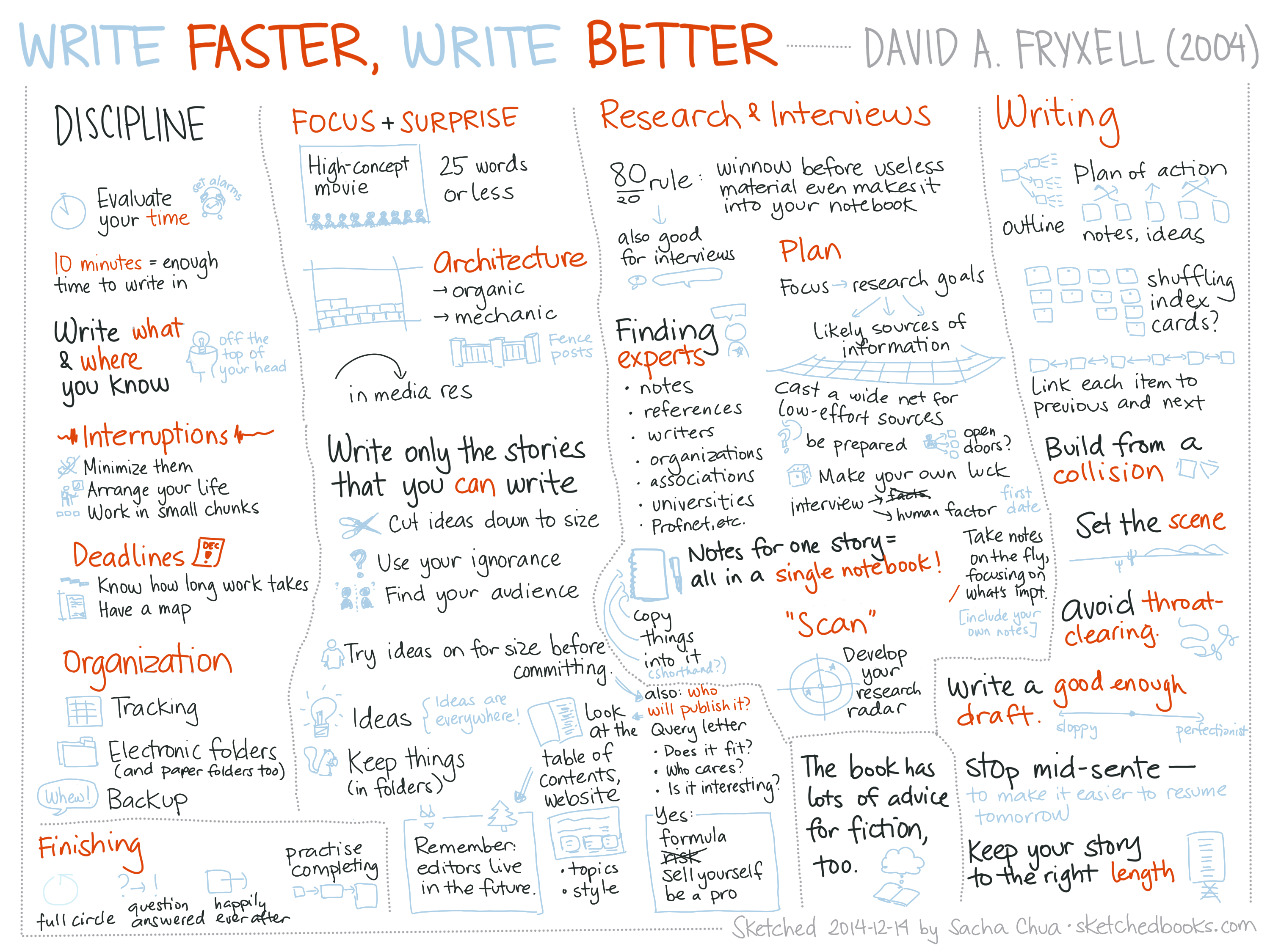

I’ve sketched the key points of the book below to make it easier to remember and share. Click on the image for a larger version that you can print if you want.

Let me think about how I feel about this book so that I can get past the initial “Yay, another book about Stoicism!”

I came across a number of anecdotes I hadn’t read before, and I liked reading stories of more modern figures instead of just the usual old chestnuts. I didn’t find any new ideas that made me stop and think; if you’re familiar with the key works in Stoic philosophy, you probably won’t get as much out of this book as someone who is completely new.

It feels oddly like the book is about this relentless drive towards a goal, but that doesn’t quite fit with what I understand about Stoic philosophy or what makes sense to me. Maybe I’m misreading the book. To me, the freedom described by Stoicism isn’t about achieving great victories after much perseverance and resourcefulness. It’s about realizing that things are what they are, you can choose how to respond to them, and thus you always have opportunities to become a better person as you learn to work with nature instead of against it–even if the path you end up taking doesn’t look like what you imagined.

It’s hard to explain the feeling I get from the drumbeat of anecdotes all throughout the book, but let me pick a passage that evokes this difference for me. The introduction (page xiv.) has this:

To act with “a reverse clause,” so there is always a way out or another route to get to where you need to go.

I could be wrong, but I think this refers to the reserve clause suggested by Seneca:

The wise man never changes his plans while the conditions under which he formed them remain the same; therefore, he never feels regret, because at the time nothing better than what he did could have been done, nor could any better decision have been arrived at than that which was made; yet he begins everything with the saving clause, “If nothing shall occur to the contrary.” … Without committing himself, he awaits the doubtful and capricious issue of events, and weighs certainty of purpose against uncertainty of result.

Seneca, On Benefits – translated by Aubrey Sewart

I understand this to mean that Stoics make well-considered decisions that anticipate opposition, but also remember that achieving goals is beyond their control. It isn’t about getting to where you need to go. It’s about being a tranquil person throughout the journey, free from being too attached to the wrong things – including fortune or misfortune.

Maybe this isn’t a book grounded in Stoic philosophy as much as it’s a motivational book that springboards from a few Stoic quotes and concepts. This is okay too. It helps me understand what I agree with and disagree with in the book, like the way I agree with and disagree with parts of Stoic philosophy.

In terms of presentation, the book’s density of stories appeals to some people and not to others. I’ve become less fond of books packed with short anecdotes. An overdose of the modern approach of aesops every other page, the shallowness and patness of the tales? In a book about obstacles, it would have been nice to see deeper struggles, maybe even with normal folks instead of famous ones; stories of frustration and suspense and everyday things that people can relate to.

I’ve long internalized the mental shift suggested by this book–of transforming obstacles and frustrations into things that can help you–but if I hadn’t, would this book help me flip that mindset? Would reading it help someone who’s struggling with perspective – would it add much more value compared to giving them a brief summary of the book? I’m not sure. If reading about other people who had it worse than you and who still achieved greater things is the sort of information you need to pick yourself up and get going, this might be a good book for you.

But I doubt that’s the case for many people who feel stuck. We’ve heard the story that the Chinese word for crisis contains the characters for danger and for opportunity (wrong, apparently). Corporate language guidelines might suggest replacing “problem” with “challenge.” Coaches exhort people to reframe their difficulties positively, listing aspects to be grateful about.

When I run into my own challenges, it’s not because I’m waiting for the perfect story or maxim to break me out. I get stuck when I don’t take a step back and really see what’s going on instead of what I think is going on. I get stuck when I don’t have a handle on the problem, when I can’t grasp it, when I can’t break it down. I get stuck when I accept the current framing instead of coming up with creative solutions. I get stuck when I’m stubborn and not listening to what the world tells me. These are all points somewhat addressed by the book, but it seemed to lack something. Perhaps I need to read it more slowly, dipping in and out of it for reflections. Although if I’m going to do that, maybe I should sit with the classics instead.

Still, there are people for whom this book is a good fit, so don’t let this talk you out of liking it. If you’ve been curious about but intimidated by Stoicism, you might try picking this up. If you’re doing okay with challenges but you want to get even better at transforming them into stepping-stones, flip through this book and meditate on its points. (Although if you’re dealing with depression, it seems remarkably insensitive to tell you to just think of your problems as good things!)