The imperfect fungibility of time: thinking about how to use money to accelerate learning

Posted: - Modified: | learningAny time I want to, I could spend more time consulting. This would make my clients happy. It would help me create much more value, and they would get more value from me than from other ways they could spend their budget. I would improve my skills along the way, especially with people's requests and feedback. And to top it all off, I would earn more money that I could add to my savings, exchange for other people's time or talents, or use to improve our quality of life.

How hard is it to resist the temptation to work on other people's things? It's like trying to focus on cooking lentils when there's a pan of fudge brownies right there, just waiting to for a bite. It's like wandering through the woods in hope of coming across something interesting when you know you can go back to the road and the road will take you to an enormous library. It's like trying to build something out of sand when there's a nifty LEGO Technic kit you can build instead. It's probably like Odysseus sailing past Sirens, if the Sirens sang, "We need you! You can help us! Plus you can totally kit out your ship and your crew with the treasures we'll give you and the experience you'll gain!"

Maybe I can use this temptation's strength against it.

Maybe I can treat client work (with its attendant rewards and recognition) as a carrot that I can have if I make good progress on my personal projects. If I hit the ground running in the morning, then I can work on client stuff in the afternoon. A two-hour span is probably a good-sized chunk of time for programming or reporting. It's not as efficient as a four-hour chunk, but it'll force me to keep good notes, and I know I can get a fair bit done in that time anyway.

The other part of this is making sure that I don't give myself too-low targets so that I can get to client work. It'll be tempting to pick a small task, do it, and say, "There, I'm done. Moving on!" But I have to sit with uncertainty and figure things out. I expect that learning to work on my own things will mean encountering and dealing with inner Resistance. I expect that my anxious side will whisper its self-doubt. So I lash myself to the mast and sail past the Sirens, heading towards (if I'm lucky!) years of wandering.

Part of this is the realization that even after my experiments with delegation, I'm still not good at converting money back into time, learning, ability, or enjoyment. Time is not really fungible, or at least I haven't figured out how to convert it efficiently. I can convert time to money through work, but I find it difficult to convert money back to time (through delegation) or use it to accelerate learning.

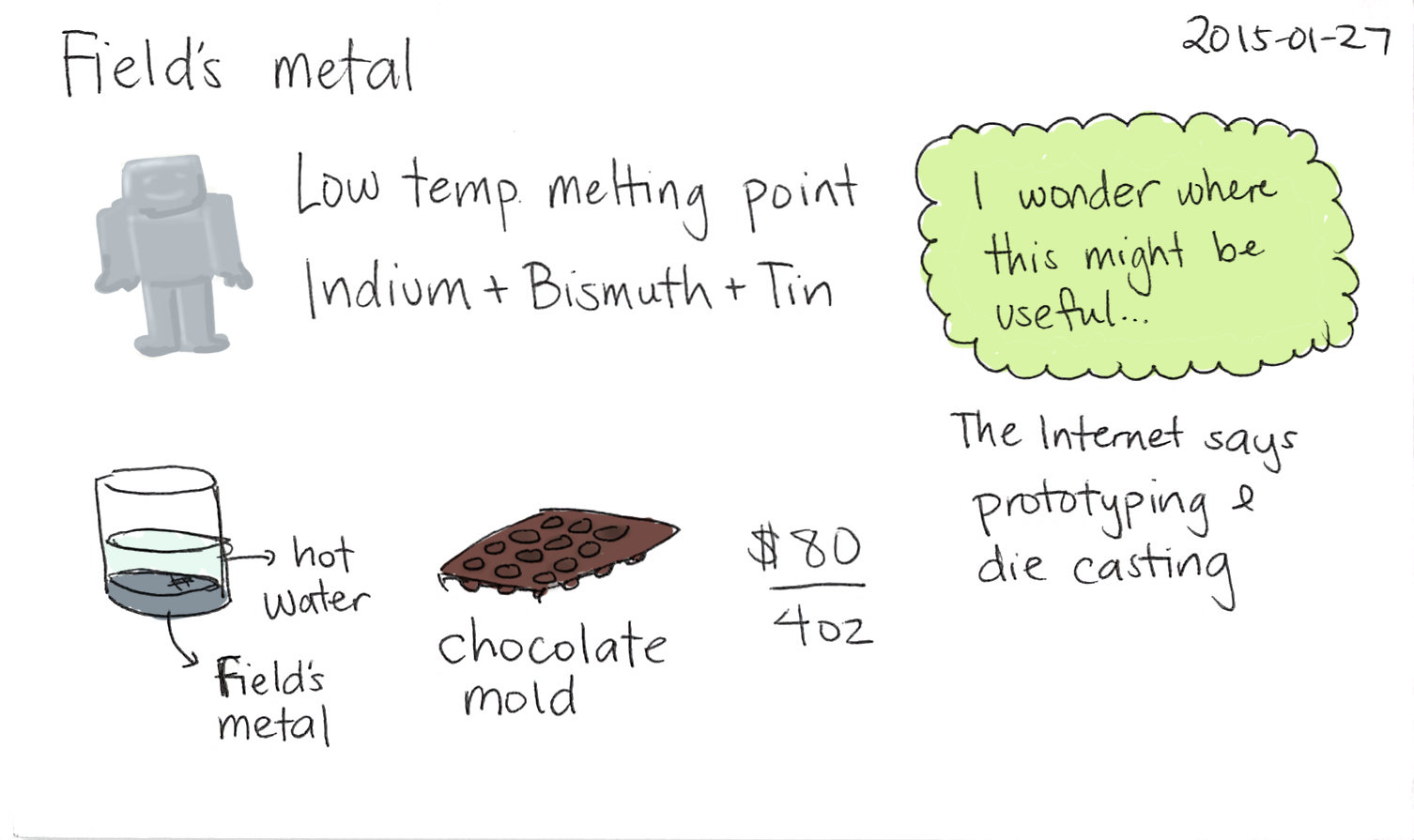

Extra money tends to go into projects, tools or cooking experiments. Gardening is one of my luxuries: a few bags of dirt, some seeds and starters, and an excuse to be outside regularly. Paying someone to do the first draft of a transcript gets around my impatience with listening to my own voice. Aside from these regular decisions, I tend to think carefully about what I spend on. Often a low-cost way of doing something also helps me learn a lot – sometimes much more than throwing money at the problem would.

But there are things that money can buy, and it's good for me to learn how to make better decisions about that. For example, a big savings goal might be "buying" more of W-'s time, saving up in case he wants to experiment with a more self-directed life as well. House maintenance projects need tools, materials, and sometimes skilled help. Cooking benefits from experimentation, better ingredients, and maybe even instruction.

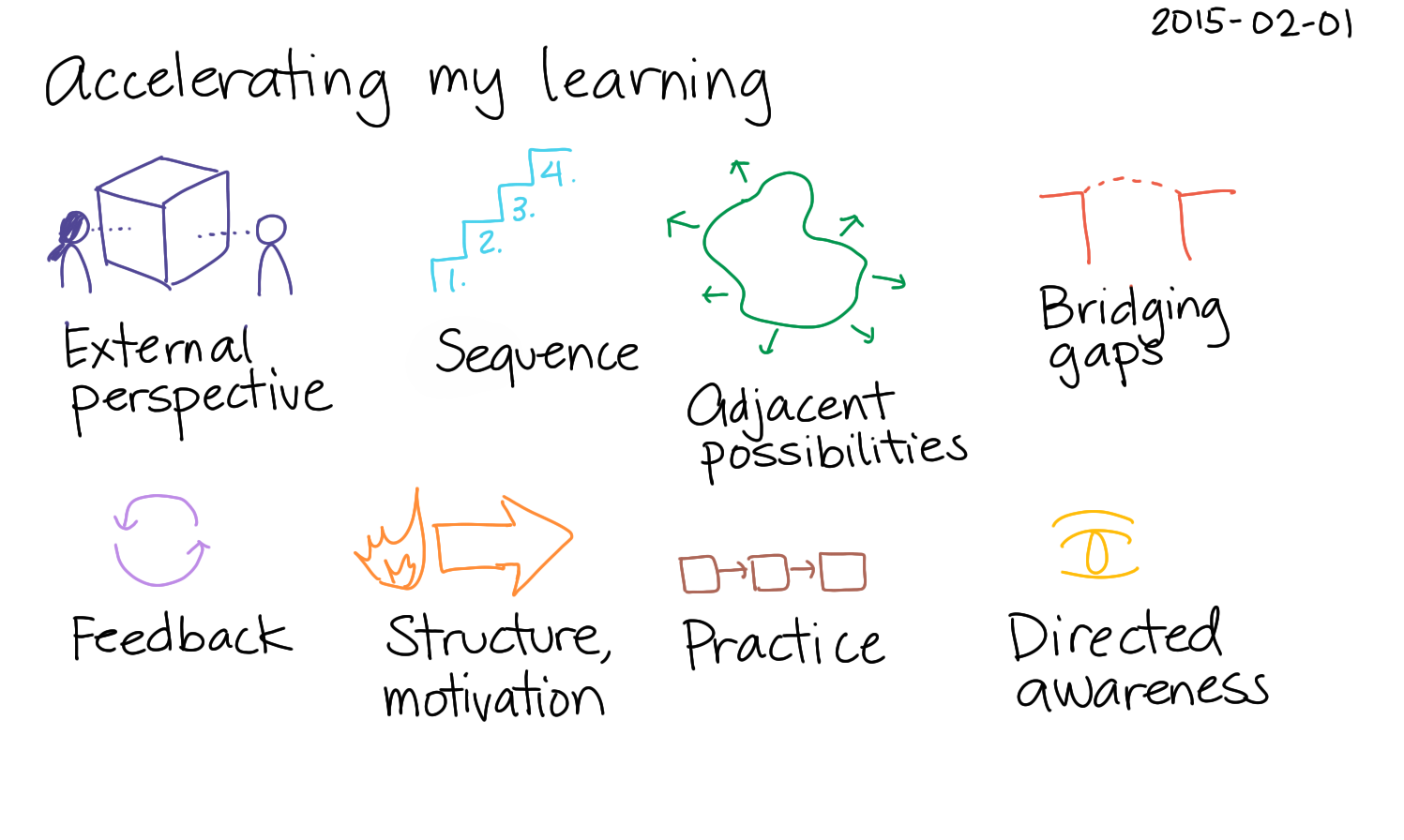

What about accelerating my learning so that I can share even more useful stuff? Working with other people can help me:

- take advantage of external perspectives (great for editing)

- organize my learning path into a more effective sequence

- learn about adjacent possibilities and low-hanging fruit

- bridge gaps

- improve through feedback

- create scaffolds/structures and feed motivation

- set up and observe deliberate practice

- direct my awareness to what's important

In order to make the most of this, I need to get better at:

- identifying what I want to learn

- identifying who I can learn from

- approaching them and setting up a relationship

- experimenting

- following up

How have I invested money into learning, and what have the results been like?

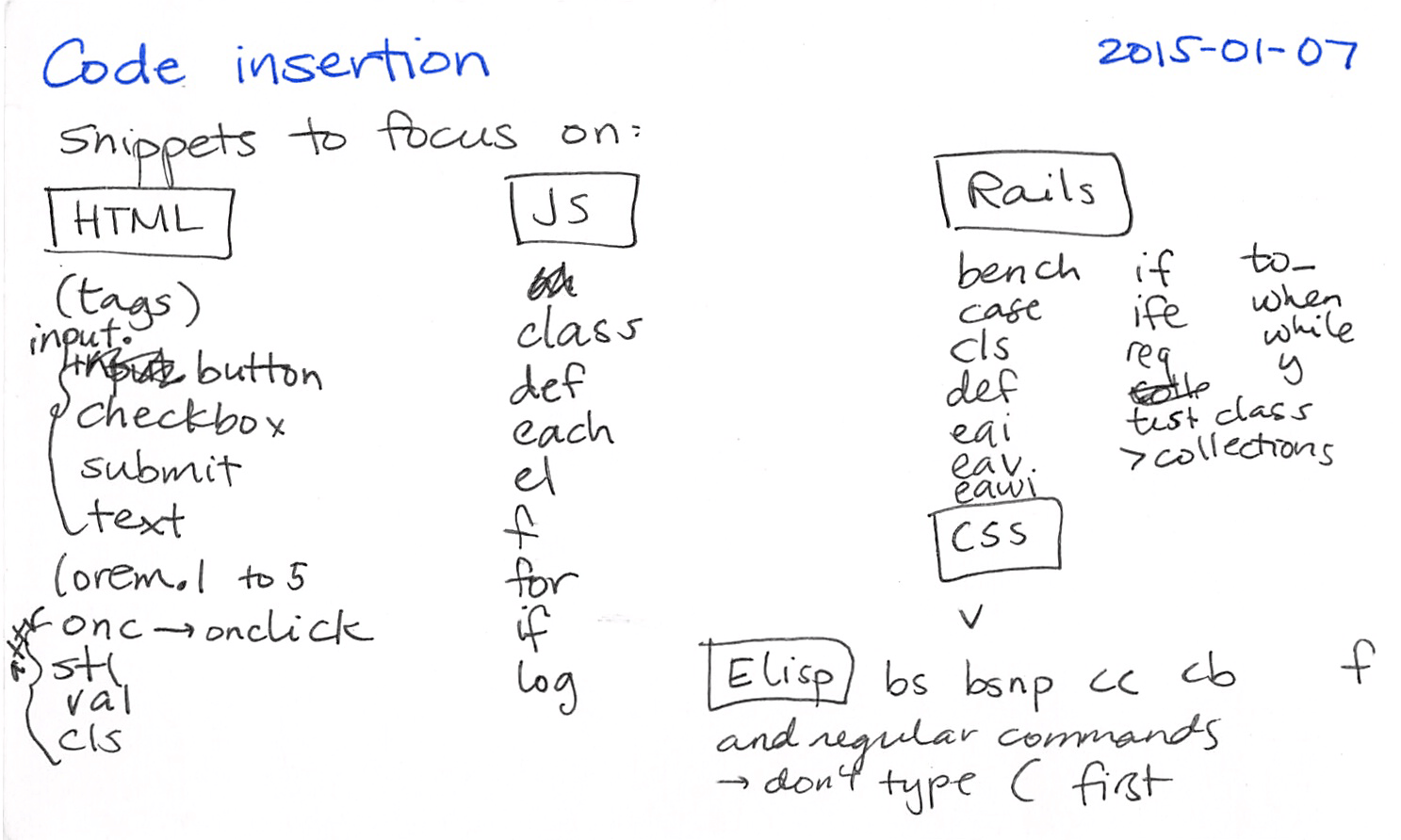

Tools? Yup, totally worth it, even for the tools I didn't end up using much of (ex: ArtRage). Do more of this. How can I get better at:

- keeping an eye out for potentially useful tools:

- Emacs packages

- AutoHotkey scripts/ideas

- Windows/Linux tools related to writing, drawing, coding

- evaluating whether a tool can fit my workflow

- supporting people who make good tools

- expressing appreciation

- contributing code

- writing about tools

- sending money

Books? Some books have been very useful. On the other hand, the library has tons of books, so I have an infinite backlog of free resources. Buying and sketchnoting new books (or going to author events) is good for connecting with authors and readers about the book du jour, but on the other hand, I also get a lot of value from focusing on classics that I want to remember.

Conferences? Mostly interesting for meeting people and bumping into them online through the years. Best if I go as a speaker (makes conversations much easier and reduces costs) and/or as a sketchnoter (long-term value creation). It would be even awesomer if I could combine this with in-person intensive learning, like a hackathon or a good workshop…

Courses? Meh. Not really impressed by the online courses I've taken so far, but then again, I don't think I'm approaching them with the right mindset either.

Things I will carve out opportunity-fund space for so that I can try more of them:

Pairing/coaching/tutoring? Tempting, especially in terms of Emacs, Node/Javascript, Rails, or Japanese. For example, some goals might be:

- Learn how to improve Emacs Lisp performance and reliability: profiling, code patterns, tests, etc.

- Define and adopt better Emacs habits

- Writing

- Organization

- Planning

- Programming

- Write more elegant and testable Javascript

- Set up best-practices Javascript/CSS/HTML/Rails environment in Emacs

- Learn how to take advantage of new features in WordPress

- Write more other-directed posts

- Get better at defining what I want to learn and reaching out to people

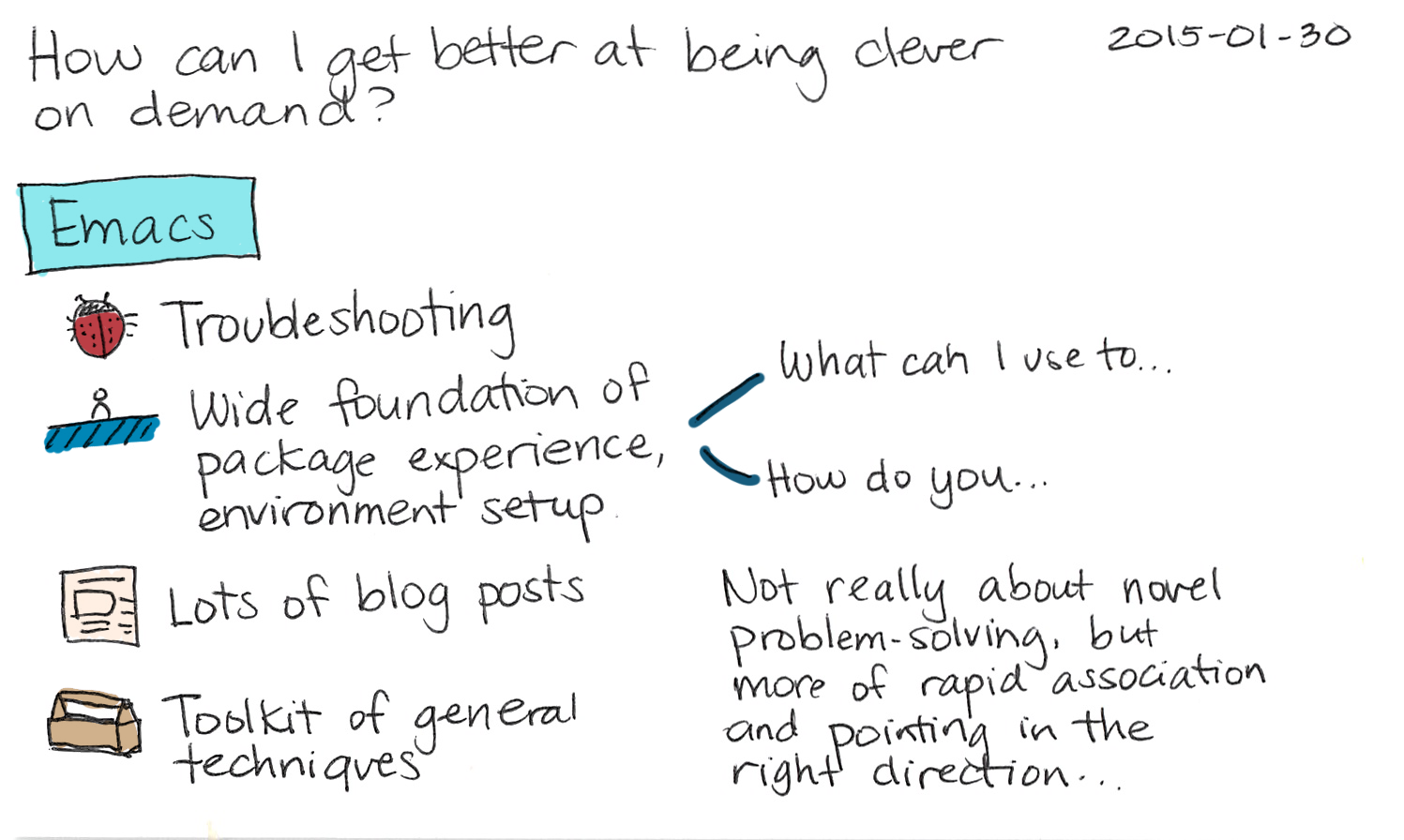

Actually, in general, how does one accelerate learning?

- General learning techniques: spaced repetition, skill breakdowns, deliberate practice…

- Structure and motivation: personal trainers, courses

- Instruction and perspective: expert, peer, or external

- Higher-quality resources: original research, well-written/organized resources, richer media, good level of detail, experience/authority

- Better tools: things are often much easier and more fun

- Experimentation: learning from experience, possibly coming up with new observations

- Feedback, analysis: experience, thoroughness

- Immersion: languages, retreats

- Outsourcing: research, summaries, scale, skills, effort

- Relationships: serendipity, connection, conversation, mentoring, sponsorship

- Community: premium courses or membership sites often offer this as a benefit

- Freedom: safety net that permits experimentation, time to focus on it instead of worrying about bills, etc.

Hmm. I have some experience in investing in better tools, higher-quality resources, experimentation, feedback/analysis, delegation, and freedom. I'd like to get better at that and at investing in relationships and outsourcing. Come to think of it, that might be more useful than focusing on learning from coaching/instruction, at least for now.

Let me imagine what using money to accelerate learning would be like:

- Relationships

- Get to know individuals faster and deeper

- Free: Build org-contacts profiles of people who are part of my tribe (people who comment/link/interact); think about them on a regular basis

- Free: Proactively reach out and explore shared interests/curiosities

- $: Figure out digital equivalent of treating people to lunch or coffee: conversation + maybe investing time into creating a good resource for them and other people + sending cash, donating to charity, or (best) cultivating reciprocal learning

- $: Sign up for a CRM that understands Gmail, Twitter, and maybe even Disqus

- Identify things to learn about and reach out to people who are good role models for those skills

- Free: Be specific about things I want to learn

- Free: Find people who know how to do those things (maybe delegate research)

- $: Possibly buy their resources, apply their advice

- $: Reach out with results and questions, maybe an offer to donate to their favourite charity

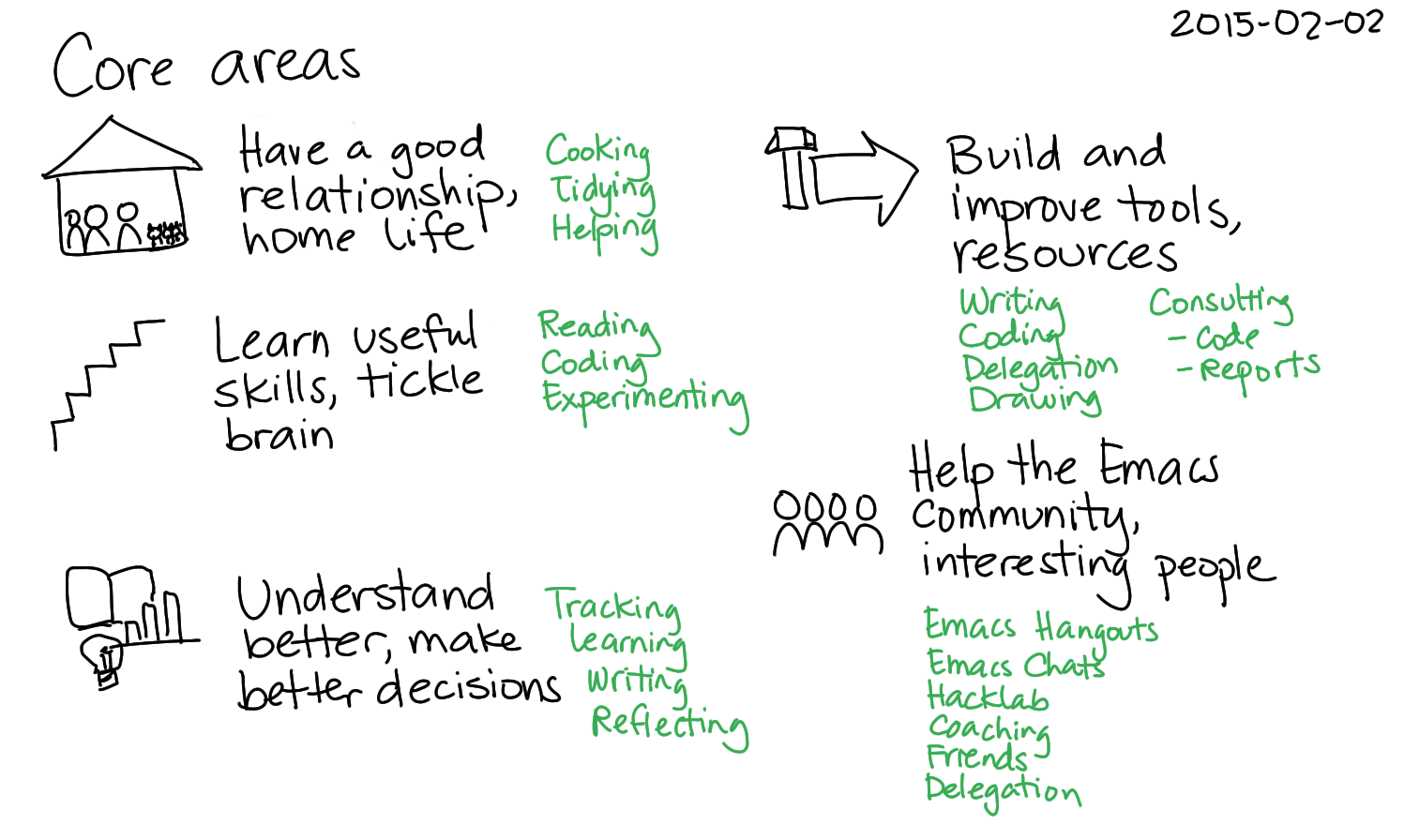

- Help the community (like Emacs evil plans; rising tide lifts all boats)

- $: Invest time and money into creating good resources

- Be approachable

- $: Bring the community together. Invest in platforms/organization. For example, I can use whatever I would have spent on airfare to create a decent virtual conference experience, or figure out the etiquette of having an assistant set up and manage Emacs Hangouts/Chats.

- Get to know individuals faster and deeper

- Outsourcing

- Identify things that I want to do, regardless of skills

- $: Experiment with outsourcing parts that I don't know how to do yet (or even the ones I can do but want external perspectives on)

- Use the results to determine what I actually want and what to learn more about; iterate as needed

Huh, that's interesting. When I start thinking about investing in learning, I tend to fixate on finding a coach because I feel a big gap around directly asking people for help. But I can invest in other ways that might be easier or more effective to start with. Hmm… Thoughts?