Alan Lin asked:

One issue I have is prioritization. I sometimes find myself spending a lot of time on low-impact activities. How do you tackle this in your life? What's the most important thing you're working on right now?

It's easy to feel that most of your time is taken up with trivial things. There's taking care of yourself and the household. There are endless tasks to check off to-do lists. There's paperwork and overhead. Sometimes it feels like you're making very little progress.

Here are some things I've learned that help me with that feeling:

- Understand and embrace your constraints.

- Lay the groundwork for action by understanding yourself.

- Act in tune with yourself.

- Accumulate gradual progress.

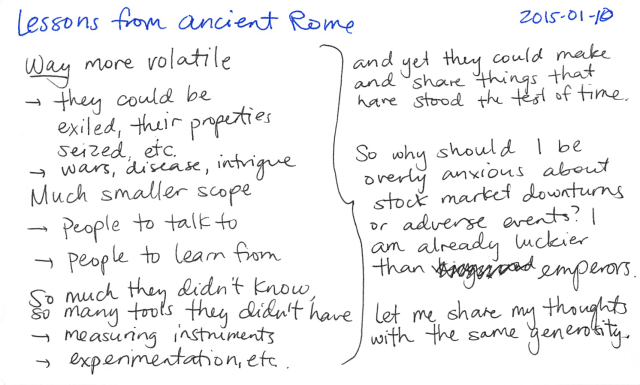

1. UNDERSTAND AND EMBRACE YOUR CONSTRAINTS

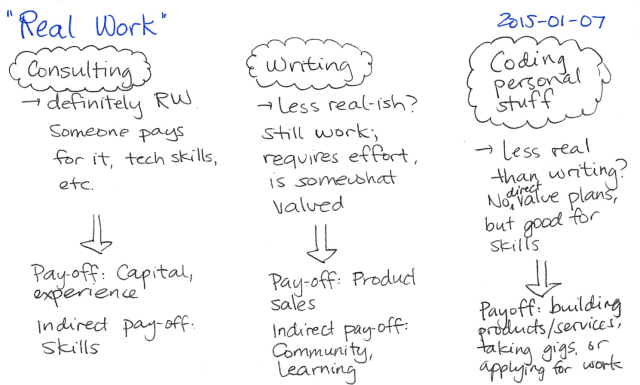

Many productivity and time management books seem to have the mindset where your Real Work is what matters and the rest of your life is what gets in the way. Sometimes it feels like the goal is to be able to work a clear, focused 60-hour or 120-hour week, to squeeze out every last bit of productivity from every last moment.

For me, the unproductive time that I spend snuggling with W- or the cats – that's Real Life right there, for me, and I'm often all too aware of how short life is. The low-impact stuff is what grounds me and makes me human. As Richard Styrman points out in this comment, if other people can focus for longer, it's because the rest of their lives don't pull on them as much. I like the things that pull on me.

Instead of fighting your constraints, understand and embrace them. You can tweak them later, but when you make plans or evaluate yourself, do so with a realistic acceptance of the different things that pull on you. Know where you're starting from. Then you can review commitments, get rid of ones that you've been keeping by default, and reaffirm the ones that you do care about. You might even find creative ways to meet your commitments with less time or effort. In any case, knowing your constraints and connecting them to the commitments behind them will make it it easier to remember and appreciate the reason why you spend time on these things.

One of my favourite ways of understanding constraints is to actually track them. Let's look at time, for example. I know I spend a lot of my time on the general running of things. A quick summary from my time-tracking gives me this breakdown of the 744 hours in Oct 2014, a fairly typical month:

| Hours |

Activity |

| 255.0 |

sleep |

| 126.3 |

consulting, because it helps me make a difference and build skills |

| 91.9 |

doing other business-related things |

| 80.5 |

chores and other unpaid work |

| 86.2 |

taking care of myself |

| 38.3 |

playing, relaxing |

| 30.4 |

family-related stuff |

| 12.6 |

socializing |

| 10.3 |

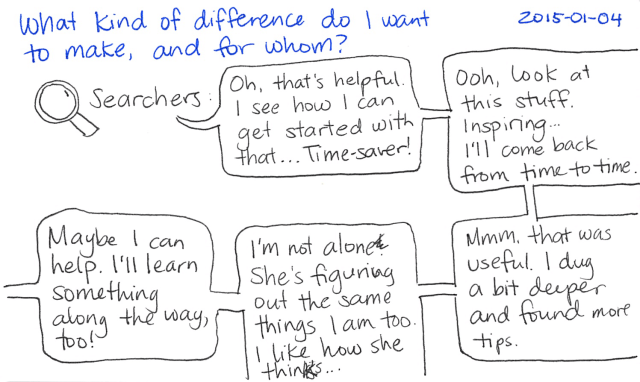

writing, because it helps me learn and connect with great people |

| 7.4 |

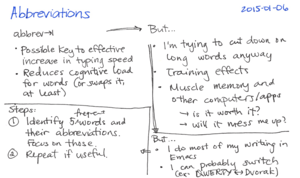

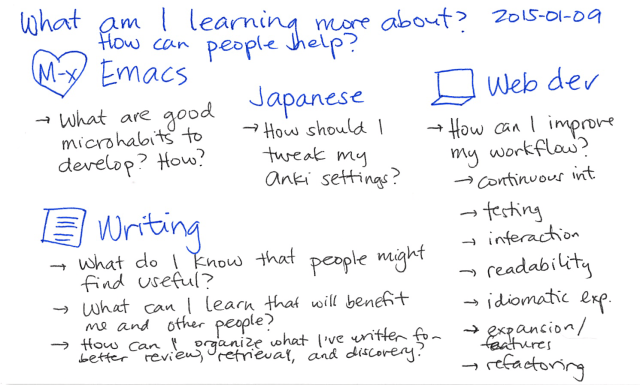

working on Emacs, because it helps me learn and connect with great people |

| 1.5 |

gardening |

| 1.0 |

reading |

| 0.5 |

tracking |

| 1.7 |

woodworking |

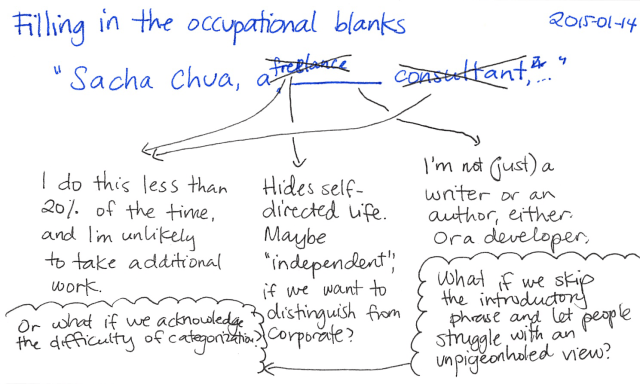

Assuming that my consulting, writing, and working on Emacs are the activities that have some impact on the wider world, that's 144 hours out of 744, or about 19% of all the time I have. This is roughly 4.5 hours a day. (And that's a generous assumption – many of the things I write are personal reflections of uncertain value to other people.)

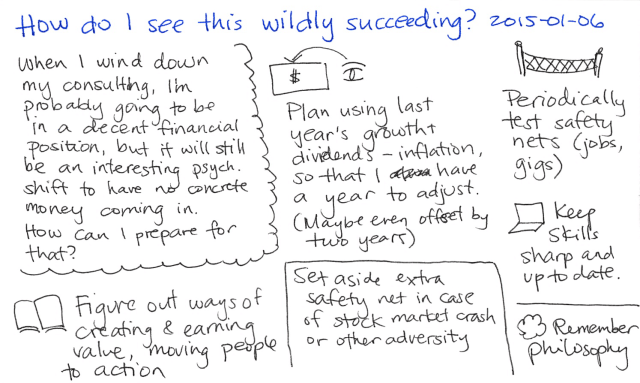

Even with tons of control over my schedule, I also spend lots of time on low-impact activities. And this is okay. I'm fine with that. I don't need to turn into a value-creating machine entirely devoted to the pursuit of one clear goal. I don't think I even can. It works for other people, but not for me. I like the time I spend cooking and helping out around the house. I like the time I spend playing with interesting ideas. I like the pace I keep.

So I'm going to start with the assumption that this is the time that I can work with instead of being frustrated with the other things that fill my life.

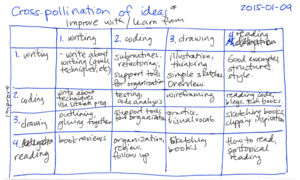

An average of 4.5 hours a day is a lot, even if it's broken up into bits and pieces. It's enough time for me to write a deep reflection, sketch one or two books, work on some code… And day after day, if I add those hours up, that can become something interesting. Of course, it would probably add up to something more impressive if I picked one thing and focused on that. But I tend to enjoy a variety of interests, so I might as well work with that instead of against it, and sometimes the combinations can be fascinating.

Accepting your constraints doesn't mean being locked into them. You can still tweak things. For example, I experiment with time-saving techniques like bulk-cooking. But starting from the perspective of accepting your limits lets you plan more realistically and minimize frustration, which means you don't have to waste energy on beating yourself up for not being superhuman. Know what you can work with, and work with that.

You might consider tracking your time for a week to see where your time really goes. You can track your time with pen and paper, a spreadsheet, or freely-available tools for smartphones. The important part is to track your time as you use it instead of relying on memory or perception. Our minds lie to us about constraints, often exaggerating what we're dealing with. Collect data and find out.

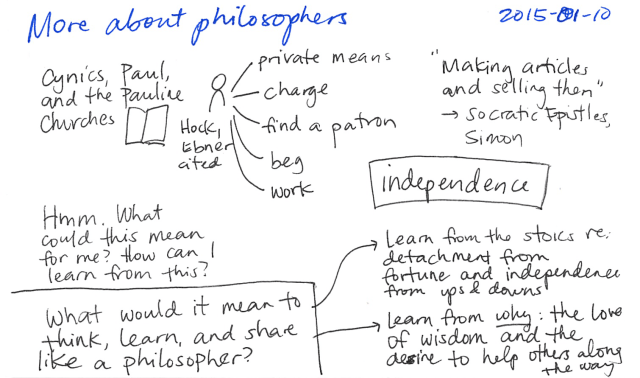

2. LAY THE GROUNDWORK FOR ACTION BY UNDERSTANDING YOURSELF

When I review my constraints and commitments, I often ask myself: “Why did I commit to this? Why is this my choice?” This understanding helps me appreciate those constraints and come up with good ways to work within them.

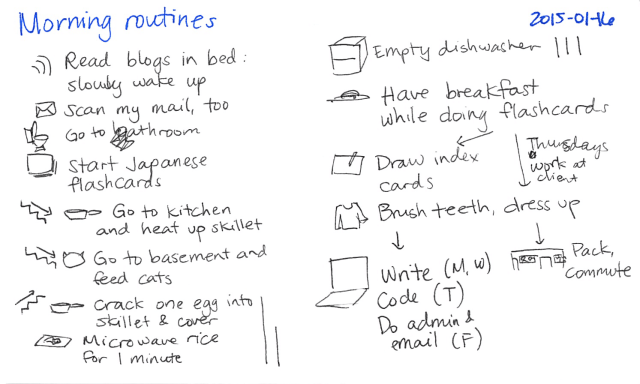

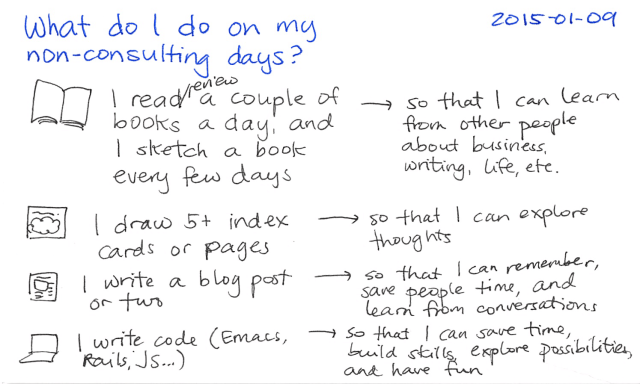

My ideal is to almost always work on whatever I feel like working on. This sounds like a recipe for procrastination, an easy way for near-term pleasurable tasks to crowd out important but tedious ones. That's where preparing my mind can make a big difference. If I can prepare a list of good things to do that's in tune with my values, then I can easily choose from that list.

Here are some questions that help me prepare:

- Why do I feel like doing various things? Is there an underlying cause or unmet need that I can address? Am I avoiding something because I don't understand it or myself well enough? Do I only think that I want something, or do I really want it? I do a lot of this thinking and planning throughout my life, so that when those awesome hours come when everything's lined up and I'm ready to make something, I can just go and do it.

- Can I deliberately direct my awareness in order to change how I feel about things by emphasizing positive aspects or de-emphasizing negative ones? What can I enjoy about the things that are good for me? What can I dislike about the things that are bad for me?

- What can I do now to make things better later? How can I take advantage of those moments when I'm focused and everything comes together? How can I make better use of normal moments? How can I make better use of the gray times too, when I'm feeling bleah?

- How can I slowly accumulate value? How can I scale up by making things available?

I think a lot about why I want to do something, because there are often many different paths that can lead to the same results. If I catch myself procrastinating a task again and again, I ask myself if I can get rid of the task or if I can get someone else to do it. If I really need to do it myself, maybe I can transform the task into something more enjoyable. If I find myself drawn to some other task instead, I ask myself why, and I learn a little more about myself in the process.

I plan for small steps, not big leaps. Small steps sneak under my threshold for intimidation – it's easier to find time and energy for a 15-minute task than for a 5-day slog.

I don't worry about whether I'm working on Important things. Instead, I try to keep a list full of small, good things that take me a little bit forward. Even if I proceed at my current pace–for example, accumulating a blog post a day–in twenty years, I'll probably be somewhere interesting.

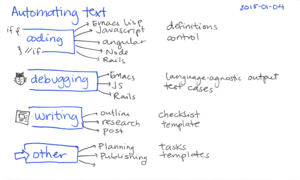

In addition to the mental work of understanding yourself and shifting your perceptions by paying deliberate attention, it's also good to prepare other things that can help you make the most of high-energy, high-concentration times. For example, even when I don't feel very creative, I can still read books and outline ideas in preparation for writing. I sketch screens and plan features when I don't feel like programming. You can probably find lots of ways you can prepare so that you can work more effectively when you want to.

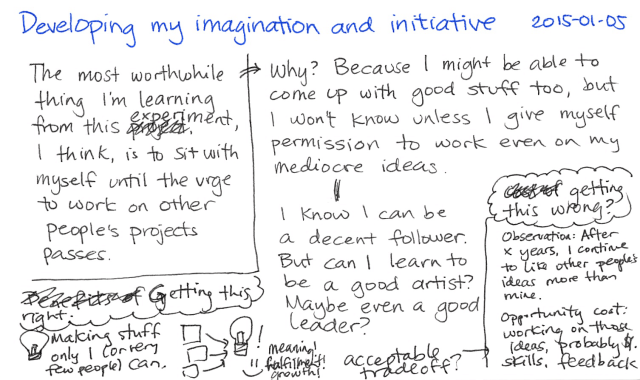

3. ACT IN TUNE WITH YOURSELF

3. ACT IN TUNE WITH YOURSELF

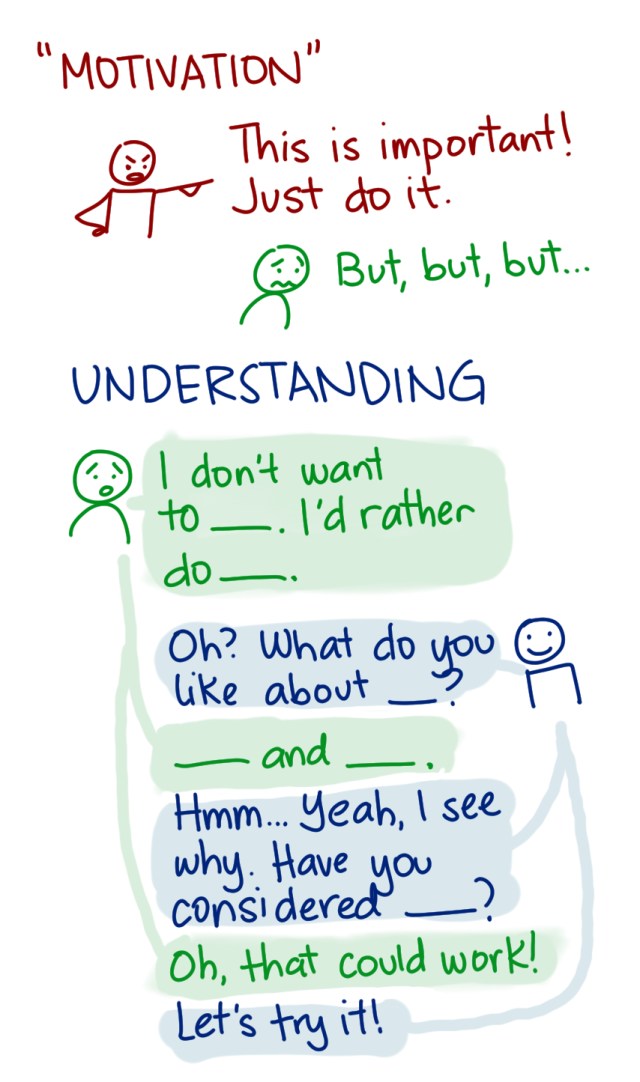

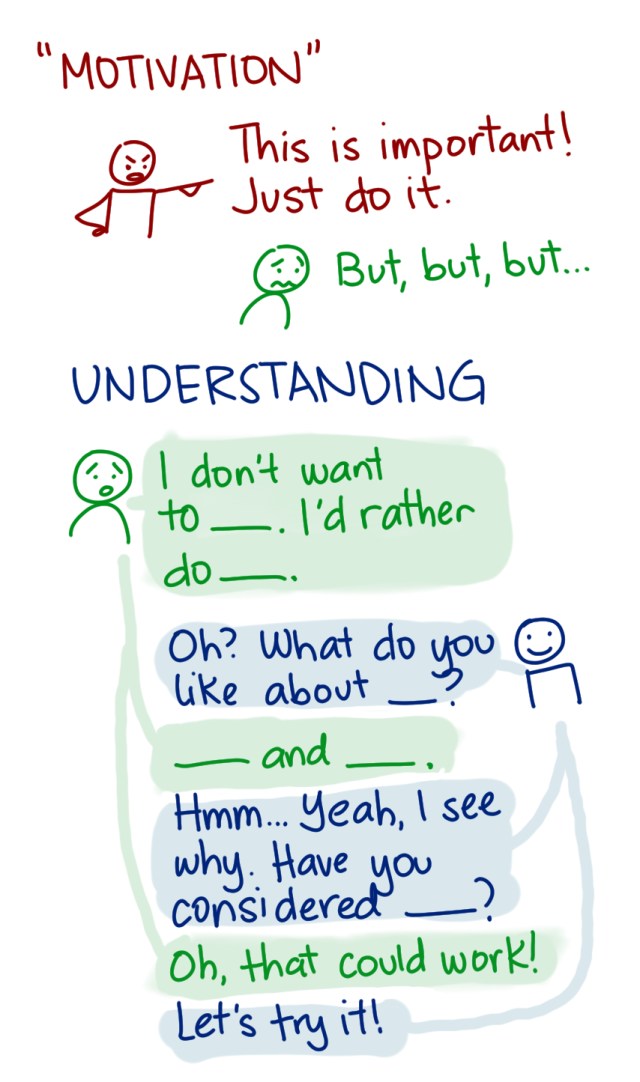

For many people, motivation seems to be about forcing yourself to do something that you had previously decided was important.

If you've laid the groundwork from step 2, however, you probably have a list of many good things that you can work on, so you can work on whatever you feel like working on now.

Encountering resistance? Have a little conversation with yourself. Find out what the core of it is, and see if you can find a creative way around that or work on some other small thing that moves you forward.

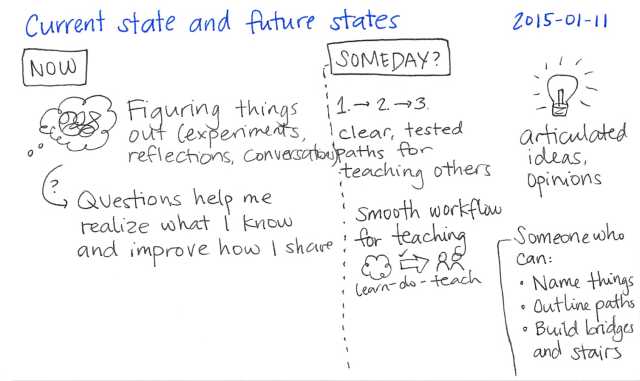

4. ACCUMULATE GRADUAL PROGRESS.

So now you're doing what you want to be doing, after having prepared so that you want to do good things. But there's still that shadow of doubt in you: “Is this going to be enough?”

It might not seem like you're making a lot of progress, especially if you're taking small steps on many different trails. This is where keeping track of your progress becomes really important. Celebrate those small accomplishments. Take notes. Your memory is fuzzy and will lie to you. It's hard to see growth when you look at it day by day. If you could use your notes (or a journal, or a blog) to look back over six months or a year, though, chances are you'll see that you've come a long way. And if you haven't, don't get frustrated; again, embrace your constraints, deepen your understanding, and keep nibbling away at what you want to do.

For me, I usually use my time to learn something, writing and drawing along the way. I've been blogging for the past twelve years or so. It's incredible how those notes have helped me remember things, and how even the little things I learn can turn out to be surprisingly useful. Step by step.

So, if you're feeling frustrated because you don't seem to be making any progress and yet you can't force yourself to work on the things that you've decided are important, try a different approach:

- Understand and embrace your constraints. Don't stress out about not being 100% productive or dedicated. Accept that there will be times when you're distracted or sick, and there will be times when you're focused and you can do lots of good stuff. Accepting this still lets you tweak your limits, but you can do that with a spirit of loving kindness instead of frustration.

- Lay the groundwork for action. Mentally prepare so that it's easier for you to want what's good for you, and prepare other things so that when you want to work on something, you can work more effectively.

- Act in tune with yourself. Don't waste energy forcing yourself through resistance. Use your preparation time to find creative ways around your blocks and come up with lots of ways you can move forward. That way, you can always choose something that's in line with how you feel.

- Accumulate gradual progress. Sometimes you only feel like you're not making any progress because you don't see how far you've come. Take notes. Better yet, share those notes. Then you can see how your journey of a thousand miles is made up of all those little steps you've been taking – and you might even be able to help out or connect with other people along the way.

Alan has a much better summary of it, though. =)

To paraphrase, you start by examining your desires because that's the only way to know if they're worthwhile pursuits. This thinking prepares you and gives you with a set of things to spend time on immediately whenever you have time, and because you understand your goals & desires and the value they add to your life, you are usually satisfied with the time you do spend.

Hope that helps!

Related posts:

Thanks to Alan for nudging me to write and revise this post!

3. ACT IN TUNE WITH YOURSELF

3. ACT IN TUNE WITH YOURSELF