Predictable advice about productivity

Posted: - Modified: | productivity, writingLet me think out loud a bit about this, since there’s something here that I want to dig into.

Someone asked me if I’d consider answering the question “What’s your morning ritual/routine that helps you stay productive and organised throughout the day?” for inclusion in a blog round-up.

Ordinarily, I’m not too keen on answering surveys or filling out questionnaires from people. I know it’s a popular content-generation technique and that bloggers like doing it because it encourages people to link, but there’s something about the format that feels a little meh. I’m even less enthusiastic about blog roundups because the typical format–a list of names, links, and a quoted paragraph or two–doesn’t lend itself well to nuanced observation or discussion.

Still, I’d been thinking about reflecting on the topic for a while, so I bumped it up my list of things to write about and drafted this: Relaxed routines.

I sent a sneak peek of the draft to the person who asked me, and he responded:

The fact that you wrote “Sometimes I think of three things I would like to do that day, and I type a few notes and thoughts into Evernote” is very interesting because other experts also think of 3 things they want to do every morning and go after them.

And I thought, no, that’s not the point I want to make. Which made me think: What is the point I want to make? I said:

When you write, don’t look for the same, old, common, generic advice. Look for what’s unusual or unintuitive or idiosyncratic.

Come to think of it, I should probably expand on this thing about slowing down, taking notes, and sharing them, since a lot of people are worried about interrupting momentum or giving away their secrets. To me, that’s more interesting than picking a few priorities for the day, which (as you noted) many other people do.

So there’s an interesting thought there that I’m going to flesh out and add to the draft. Perhaps by the time you read this, I’ll have already added and posted it.

Anyway. This got me thinking about the predictability of most productivity advice. If I crack open a newly-published book on productivity or click on one of the countless blog posts that flow into my streams, I know that more likely than not, it will tell me to: Wake up early. Prioritize. Don’t start with e-mail. Take care of your health.

It’s about as surprising as reading a personal finance book that tells me to spend less than I earn. Granted, there are probably lots of people for whom the repetition of these concepts helps.

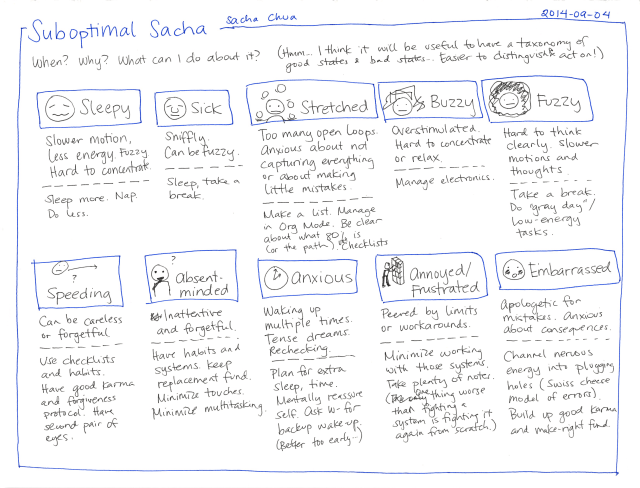

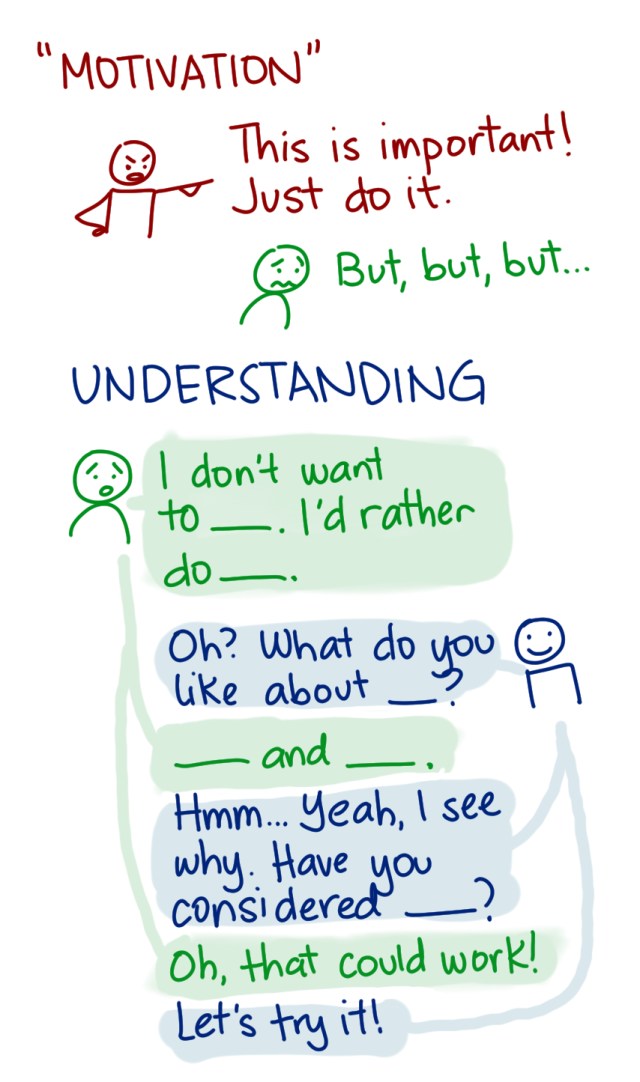

I wonder how to go beyond the same old advice. What kinds of information have been helpful for me when I want to change? What would be more helpful for other people? How can I go beyond writing generic thoughts myself? How can I notice and dig into the differences? How can I learn from more divergences?

Here’s what I’ve found helpful:

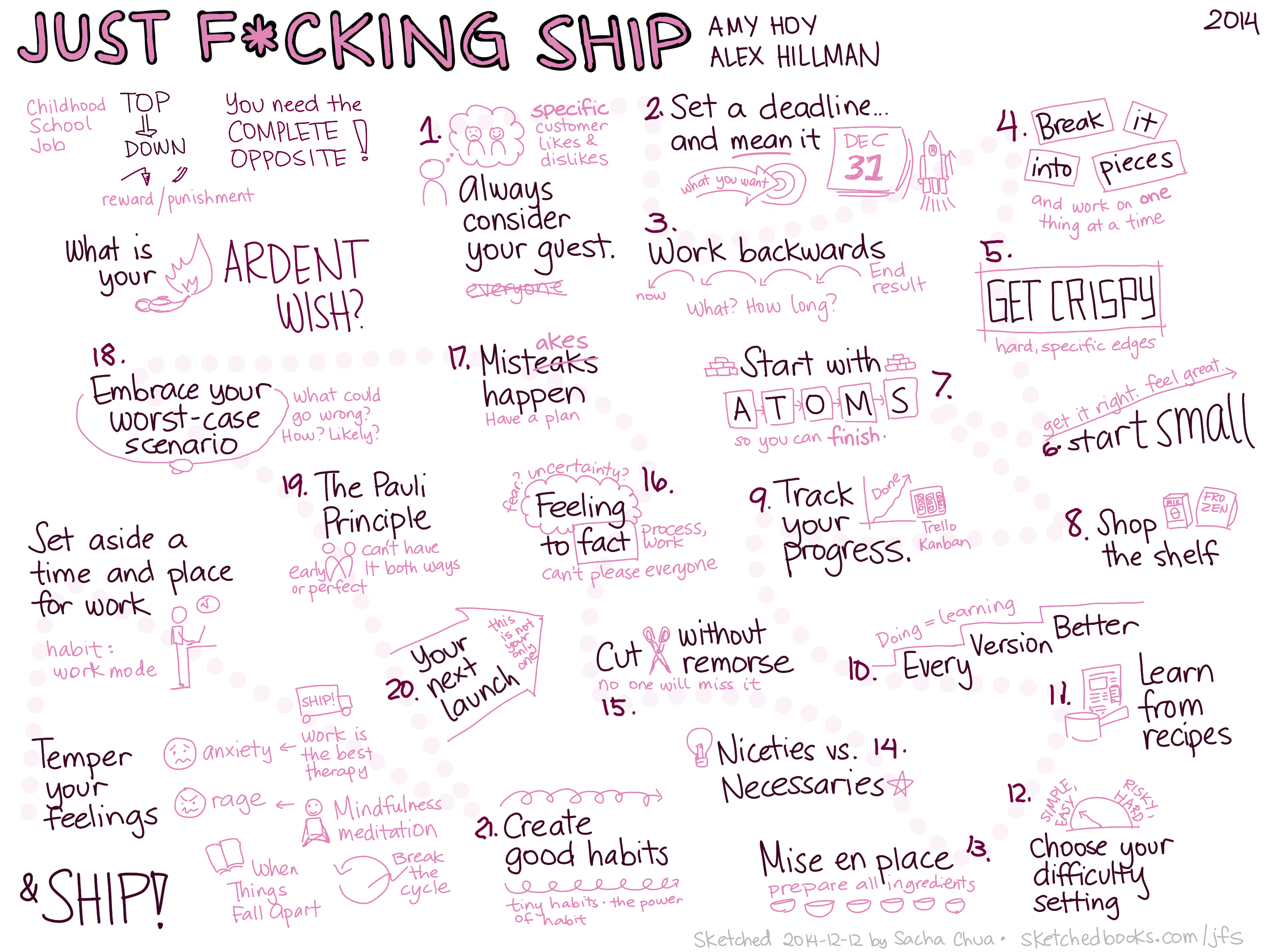

- Collections of different approaches, so that I can experiment and find out what works for me. I don’t read books looking for the One True Way to manage your tasks. I look for the diversity of systems described by different people so that I can extract ideas that I can play around with. That also means that I don’t want trite advice that I already have previous samples of. I’m looking for new stuff, things to make me go “Hmm, let me try that.”

- Pointers to interesting people, which is related to the first benefit. For example, when reading about how scholars managed information before computers (Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information Before the Modern Age), I came across historical role models like Seneca and Pliny. That led me to learn more about their stories so that I could understand their techniques in context. It isn’t just about isolated pieces of advice, but people whose lives that advice came from and why they learned that. Plus points for people I can identify with or be inspired by: “Oh, she did that, so I can probably pull off something similar too!”

- Behind-the-scenes thoughts: Reading people’s thoughts about their own systems is more interesting for me than reading people’s conjectures about other people’s secrets. I like reading blog posts from people who are thinking out loud, because that lets me peek into other people’s thought processes and watch how they learn. I like seeing the in-between stuff, not just the polished products.

- Reflection questions, so that I can direct my awareness to things I might otherwise overlook, and so that I can evaluate things.

- Research, particularly with non-intuitive results. For example, applied psychology tells us our brain is subject to all sorts of fallacies, and being aware of things like sunk cost fallacy helps me try to correct for them.

So with that in mind, how can I improve that reflection on routines so that I and other people can get more value from it?

Let me think about potential points of divergence from common wisdom, and why I’ve chosen those ways:

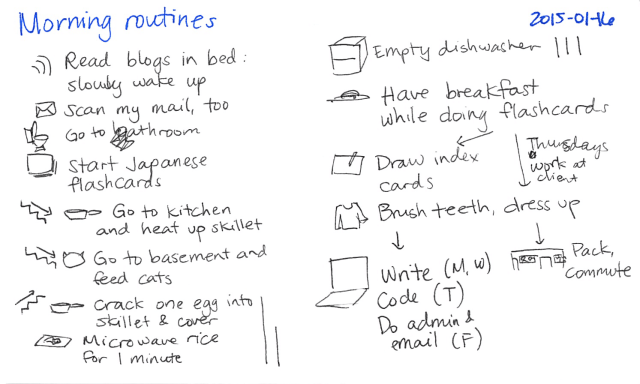

- I sleep in instead of getting up early. For me, it’s important to mostly go to bed at the same time W- goes to bed (unless he’s staying up really late). Since that’s usually between 12 AM to 1 AM and I need a bit more than 8 hours to feel well-rested, this means I usually get up between 8:30 and 9:30. I organize the rest of my schedule around this, including avoiding all morning meetings.

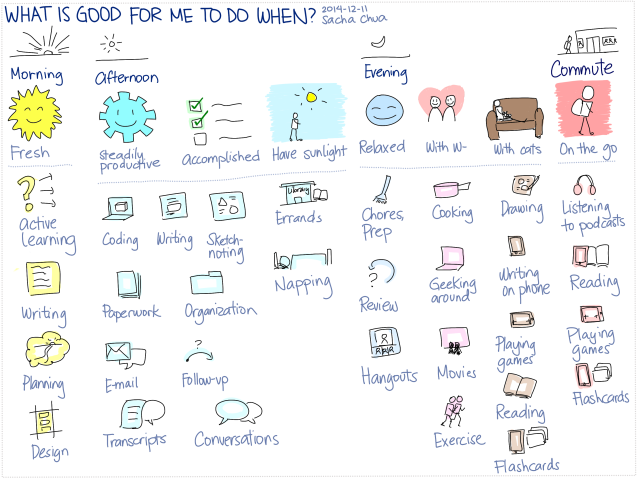

- I follow my energy instead of forcing myself to stick to a plan. I used to block off time to work on specific things, but I realized that I enjoy flexibility and I work better with an open schedule. More about this.

- I don’t make specific, measurable, time-bound goals. I found that I’m not motivated by “urgent” deadlines that I set myself. Instead, I keep a large list of small tasks, and I use those to keep moving forward on different things.

- I slow down to take notes. Many people tell me they don’t have the time to take notes. I make note-taking part of the way I do things, whether it’s thinking about a decision, learning about a new topic, or debugging a problem. It’s not really slowing down, actually. I suspect that I make slower progress when I don’t take notes, because my mind gets more jittery and has to cover the same ground repeatedly.

- I share what I’m learning. People are often concerned about giving away their secrets, looking foolish, or letting go of competitive advantages. I find that blogging helps me learn more, connect with interesting people, and get more stuff done.

- I don’t worry about being responsive. I’m very casual about responding to e-mail and blog comments. I can go a week or two (and sometimes more!) before replying, although I check more frequently than that. I treat them as long-term asynchronous conversations, not as firm commitments. This lets me see my e-mail mostly positively as a source of interesting questions and ideas, rather than as an obligation that gets in the way of Real Work.

- It’s easy for me to choose slack over status or stuff. This is more of a personal finance thing, I think. I’m picky about the things I swap my life for, because I prefer space, freedom, and resisting hedonic adaptation. This is why it’s easy for me to ignore advertising.

- I’ve shut up the “You’re not an artist!” internal self-censor so that I can use visual thinking to explore ideas. People often tell me that they wish they could draw sketchnotes too. Pointing out that I draw like a 5-year-old still doesn’t seem to be enough to help them get over that mental barrier. Someday I’ll probably figure out how to help people hack around that.

For each of these choices, there are probably thousands of other people (at least) who do the same thing. That’s okay. In fact, that’s terrific, because then we can swap notes. =) I don’t have to say totally unique things. I’m not sure I can. I just want to add more to the conversation than generic “advice.”

So how do those choices influence my everyday routines? Well, waking up when I feel like it is an obvious one. Writing, drawing, and publishing throughout the day is another. This 5-year experiment is another result of those choices.

The most useful change that people can experiment with, I think, is the one of writing stuff down, even if they don’t publish it. Not just plans and reviews (although those are good places to start), but the in-between stuff, the “I’m not entirely sure where I’m going with this” stuff. It could be a text file or a document or a paper notebook – just somewhere you can leave breadcrumbs for your brain so that you can come back to things after interruptions and so that you can go back in time.

But journaling is also part of the set of standard productivity advice, so what can I add here? The reassurance that no, it doesn’t make you go slower, it actually lets you cover more ground? A demonstration, so that people can see what that looks like (especially over years)? Workflow tweaks to better integrate it into the way you do things? Personal knowledge management ideas for organization? Surveys of other people’s systems so that we can pick up great ideas?

If I want some fraction of the people who read me to pick up this writing habit, what I can do to help them (you!) get over any barriers or excuses?

That’s what I should write. I’m not going to be able to trigger that epiphany in one excerpted paragraph in a list of twenty or fifty or people. But I can always explore the idea on this blog (with your help =) ), and other people can link to or summarize whatever they want, and who knows what conversations can grow.

3. ACT IN TUNE WITH YOURSELF

3. ACT IN TUNE WITH YOURSELF