How do you learn? What’s your process like? What helps you learn more effectively? Timothy Kenny put together this learning profile based on almost 30 of my blog posts and pages throughout the years. Some of his observations are still true today, while others are a little out of date or incomplete. (For example: I’m back to feeling a visceral horror at the thought of marking up my books, and I don’t use a special keyboard.) Since quite a few people are interested in learning about learning, I thought I’d write about what I find helpful and how I want to improve.

MINDSET

1. It starts with attitude

I learn better when I’m learning something I care about and I can celebrate small successes. I can see this difference more clearly by looking at where I’ve had problems. I’ve struggled with learning when I didn’t start off with that engagement and feeling of possible competence. In my English literature classes, I felt like a fake trying to write critical essays. (“Irony? I don’t do irony, I’m a programmer!”) In calculus, I fell behind in memorizing and understanding different principles, so it was harder and harder to catch up. Most of my consulting engagements were fun, but I hated dealing with enterprise software stacks or Microsoft SQL Server administration because feedback was slow and I didn’t have that small kernel of confidence to build on.

Sometimes, when I’m trying to figure out something complex (say, statistical analysis, D3 Javascript visualizations, tax rules in Canada), I remind myself: other people have figured this out before, so I’ll probably be able to do so too. That helps.

When I catch myself making excuses why I’d have a hard time learning something, that’s useful information. I’m avoiding it for a reason, sometimes several reasons. What are those reasons, and what can I do about it? I don’t allow myself to say that I can’t learn something. I have to face the facts. Either I haven’t broken it down into a small enough chunk to learn, or I don’t care about it enough. If I don’t care about it enough, then I look for ways to work around it. I don’t have to learn everything, but I need to believe that I can learn what I need to.

Tip: Watch out for your excuses. Deal with them, or be okay with dropping things you don’t care about.

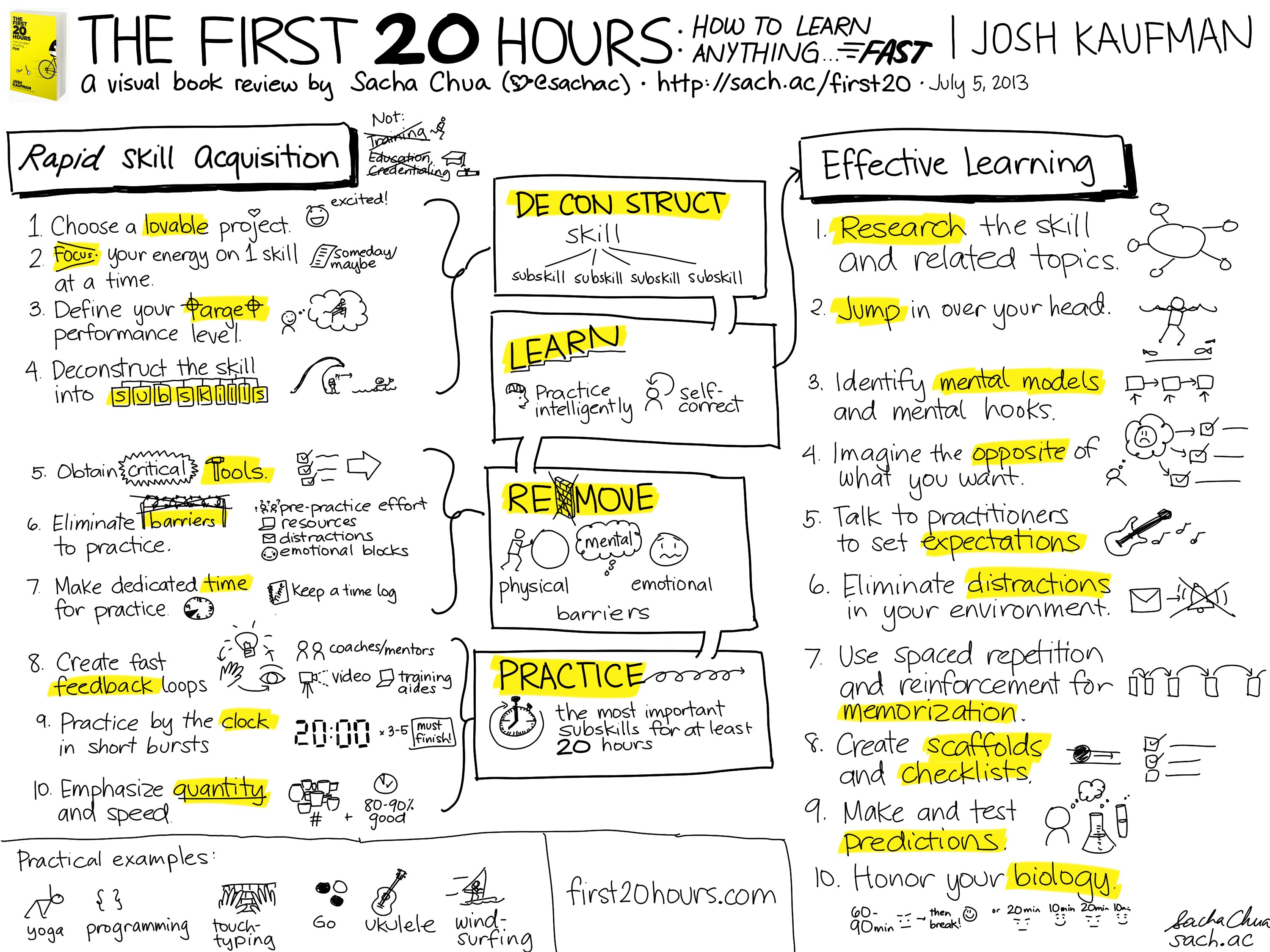

2. Work with your brain, not against it

We learn in different ways. I find it difficult to sit still and listen, so I fell asleep in many of my university lectures, and I’m not really into online courses or podcasts. My memory is fuzzy, so taking notes and searching them helps a lot. I can find it tiring to concentrate on one thing for more than four hours, so I keep a list of things to learn more about. I love reading, and I love trying things out for myself. Spaced repetition seems to work well for me in terms of memorizing, while small tasks work well for me in terms of learning something new.

Tip: Know your brain’s quirks and limitations, and work with them.

3. Embrace uncertainty and intimidation

It’s hard to learn when you don’t know where to start, what’s involved, or what’s possible. I’m learning to embrace that uncertainty. Uncertainty is awesome. It means there’s lots to learn. You don’t have to completely resolve uncertainty – small experiments can give you plenty of information.

Intimidation can be good, too. Even if a topic looks too large to handle, if you can break it down into smaller chunks that you can learn and you celebrate that progress, it can feel fantastic.

Tip: The important thing here is not to avoid the topic just because you don’t know enough about it. Get your teeth into it and start chewing. That’s the point of learning, after all.

4. See learning opportunities at many levels

If you can get better at recognizing learning opportunities, then you can wring more learning out of the same 24 hours we get in a day. This is mostly about mental friction. For example, Canada Post recently lost my passport. I could spend time and energy getting really annoyed about that (which wouldn’t do anything), or I could focus on learning from it. Everything is a learning opportunity.

It gets even better when you can recognize multiple levels of learning opportunities. The same experience can teach you many different things. For example, attending presentations can be a hit-or-miss experience. Sometimes I go to an event and the presentation covers something I already know, or the speaker isn’t engaging, or there’s not enough time for Q&A. Many people would think that’s a waste of time. But I get a lot of value even if the talk doesn’t meet my expectations: drawing practice, connection opportunities, raw material for blog posts and communities, reflections on what would make the presentation more effective… It’s like getting several hours’ worth out of one hour.

Tip: See each experience as a learning opportunity, and wring out of it as much as you can.

5. Think about thinking, learn about learning – observe and improve your processes

If you can reflect on and observe yourself, it’s easier to improve how you work. Words help you understand and communicate. I read books and research papers on thinking, and recognizing my processes helps me articulate them and tweak them.

PROCESS

6. Break things down into small chunks, and write down your questions

You have to start somewhere, and besides, it’s more fun when you can celebrate along the way. A question is a good unit to work with. You can break large questions down into smaller questions. I try to get things down into questions that I can answer within four hours. Questions give you focus, and they often suggest ways to answer them as well.

Writing down your questions helps a lot. It means you never run out of things to learn, you don’t have to worry about forgetting an interesting idea while you’re focused on something else, and you can review your progress as you go along.

7. Reduce friction

Make it easy to learn. For me, annoyance, frustration, and intimidation cause mental friction, so I try to avoid them unless I can use those emotions to fuel my motivation. It’s worth reducing environmental friction, too. Make it easy to get started and keep on going. For example, I’m learning Japanese. I have Japanese flashcards on my phone so that I can learn anywhere instead of needing to be at home with a textbook. Set things up so that learning is the path of least resistance.

8. Experiment

It can be surprisingly easy to try something out with minimal risk and see what happens.

I like thinking about the grand experiment of life. Worst-case scenario, even if one of my experiments turns out badly, my notes might be able to help someone else make a better decision.

9. Notice the unusual

Getting into the habit of making small predictions will help you notice when things are different from what you expect. More learning opportunities there!

It’s also useful to look at familiar things in a new light. Anything can be amazing if you look at it from the right perspective. I’m working on learning how to fix a rice cooker, and rice cookers are pretty darn cool.

10. Build in feedback

Learning is faster when you have quick, reliable feedback. This is one of the reasons why I like programming so much: you can do something, see the results, change it a little, and see the new results. Whenever possible, build short feedback loops into how you learn. (Hmm; I should see about experimenting with having an editor again…)

11. Take advantage of other people (in a good way)

Other people have probably learned what you’re trying to learn, so learn from them if possible. This is why I like reading books and blog posts, having mentors, and asking questions. One of the surprising benefits of having a blog is that other people help you remember really old posts, too.

12. Do something with what you learn

It’s not yours until you do something with it. You can start by summarizing it in your own words, but the best thing to do is to apply it to your life or make something with it. Then you’ll have better questions and you’ll understand it more.

13. Relate what you’re learning to what you know

The human brain is really good at association. If you start a sentence with “_(thing that you’re learning)_ is like _(something you know)_ because…”, chances are that you can finish the sentence easily. Seeing the connections helps you build your confidence and lets you take advantage of transferrable skills.

Don’t believe it? Here are some examples from my life: sketchnoting is like computer programming because they’re both about simplifying concepts so that I can communicate them with a limited vocabulary and a logical layout. Writing is like biking because it helps to have a map of where you’re going, but you can take different routes to get there, and you can make some interesting discoveries if you try different routes.

Analogize away.

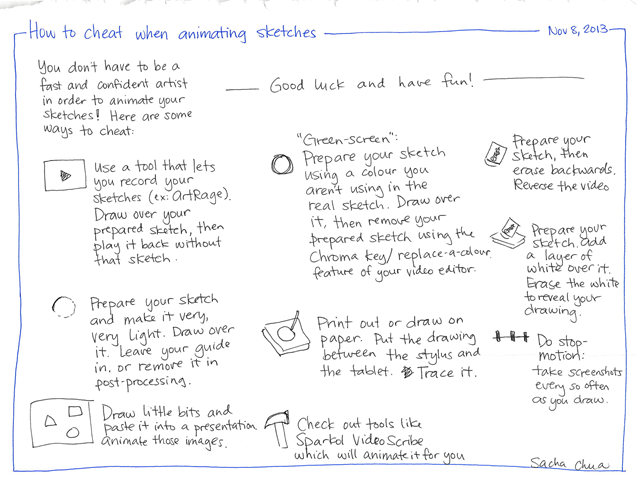

14. Take notes and review them (and share them, if you can!)

People’s brains are terrible at remembering things. I can’t remember the details of what I did last week, much less what I learned four years ago. Take notes so that you can remember. This applies even if you can easily go back to the original material, like books, presentation slides, or videos. Sure, you might have a copy of the content, but you might not remember what you felt, what you decided to do about it, what you learned, what you were surprised by, and so on.

Writing notes that other people will read forces you to understand things better. I find that visual notes capture less detail, but are faster and more fun to review, so I take lots of them.

15. Practise continuous improvement

Tiny improvements can lead to big changes over time. Experiment. Try things out. Notice where you’re doing well, and where you can improve. Tweak the way you learn.

For example, I’m learning more about outlining now. Looks promising!

16. Celebrate progress

This makes the journey fun. Notes and plans help here too. Every so often, take a look back and see how far you’ve come, and plan a little ahead so that you know where you want to go next.

—

So those are some things I’ve learned about learning. I’ll write about specific tools and techniques in a future post. More about reading, outlines, sketchnotes, mindmaps, transcripts, asking, and so on – next time!

Update 2013/07/22: Here’s my breakdown of different skills involved in learning.